0.7: Quadratics

Whereas polynomials are prevalent in many applications, linear and quadratic polynomials arise most frequently in practical modeling and approximation. In Section 0.5 we considered linear functions (first-degree polynomials) and their graphs. This section provides a similar overview of quadratic functions (second-degree polynomials) through the following topics:

Graphs of Quadratic Functions

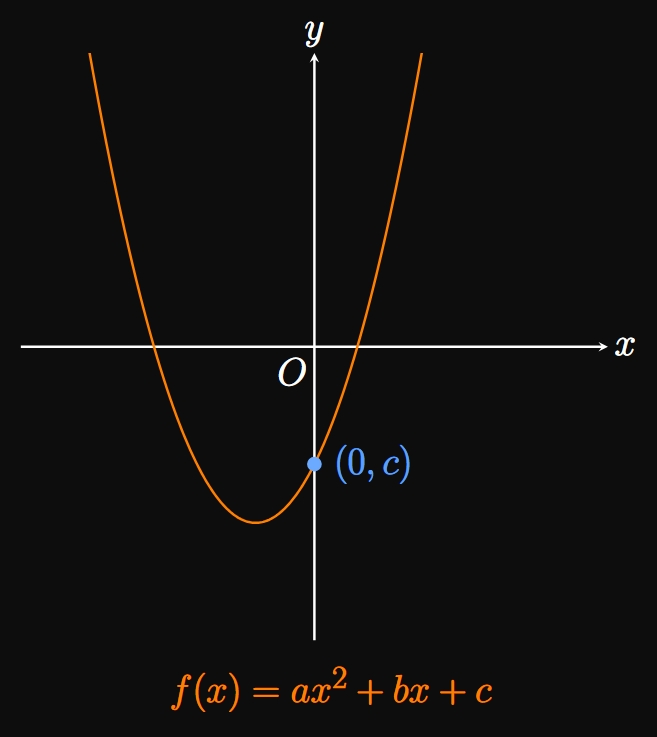

A quadratic function is a second-degree polynomial whose graph is a parabola: a symmetrical U-shaped curve. The general form of a quadratic is \begin{equation} f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c \label{eq:standard-form} \end{equation} where \(a \ne 0\) is the leading coefficient of \(f\) and \((0, c)\) is the \(y\)-intercept, the point at which the graph of \(y = f(x)\) crosses the \(y\)-axis (Figure 1A). If \(a \gt 0,\) then the parabola opens upward; if \(a \lt 0,\) then the parabola opens downward.

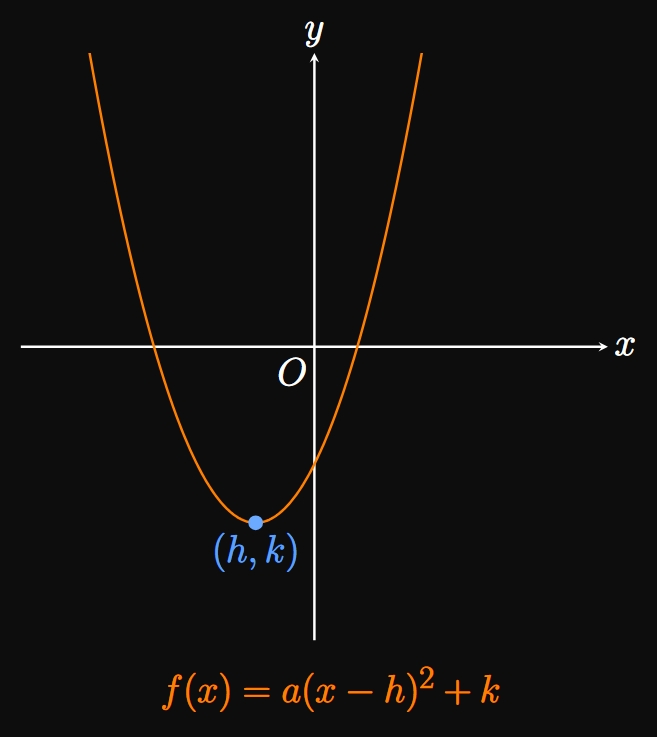

\(\eqrefer{eq:standard-form}\) can be manipulated into two other forms. By factorization, a quadratic function can be written in intercept form: \begin{equation} f(x) = a(x - p)(x - q) \cma \label{eq:intercept-form} \end{equation} where \(p\) and \(q\) are the zeros of \(y = f(x).\) Geometrically, the graph has \(x\)-intercepts at \((p, 0)\) and \((q, 0)\) (Figure 1B), as you may verify by substituting \(x = p\) and \(x = q\) in \(\eqref{eq:intercept-form}.\) Lastly, the vertex form is \begin{equation} f(x) = a(x - h)^2 + k \cma \label{eq:vertex-form} \end{equation} where \((h, k)\) is the vertex, the lowest or highest point on the parabola (Figure 1C). We call the vertical line \(x = h\) the axis of symmetry, the line about which the graph of \(y = f(x)\) is symmetric. \(\eqrefer{eq:vertex-form}\) can be attained from \(\eqref{eq:standard-form}\) using the formula \[h = -\frac{b}{2a} \pd\] In any of these three forms, if \(a\) is negative, then the parabola opens downward and the vertex is a maximum.

- The general form is \begin{equation} f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c \cma \eqlabel{eq:standard-form} \end{equation} where \((0, c)\) is the \(y\)-intercept of the parabola.

- The intercept form is \begin{equation} f(x) = a(x - p)(x - q) \cma \eqlabel{eq:intercept-form} \end{equation} where \(p\) and \(q\) are zeros of \(y = f(x).\)

- The vertex form is \begin{equation} f(x) = a(x - h)^2 + k \cma \eqlabel{eq:vertex-form} \end{equation} where \((h, k)\) is the vertex, the lowest or highest point on the parabola, and the axis of symmetry is \(x = h,\) where \(h = -b/2a.\)

Intercept Form By factorization (Section 0.1), we have \[ \ba f(x) &= -2(x^2 - 4x + 3) \nl &= \boxed{-2 (x - 3)(x - 1)} \ea \] (The greatest common factor is \(-2,\) which we extracted first.)

Vertex Form In \(\eqref{eq:vertex-form},\) we have \[h = -\frac{b}{2a} = -\frac{8}{2(-2)} = 2 \pd\] We see \[ f(2) = -2(2)^2 + 8(2) - 6 = 2 \pd \] Thus, \(k = 2.\) The vertex form is therefore \[f(x) = \boxed{-2(x - 2)^2 + 2}\]

Graph Several features of the graph are apparent from the different forms of \(f.\) From the general form, the \(y\)-intercept is seen to be \((0, c) = (0, -6).\) Additionally, from the intercept form, the \(x\)-intercepts are \((1, 0)\) and \((3, 0).\) Lastly, from the vertex form, the vertex is \((2, 2).\) Because \(a \lt 0,\) the parabola opens downward and the vertex is the location of the maximum. The graph of \(y = f(x)\) is shown in Figure 2.

Completing the Square

Another systematic method of converting a quadratic expression from general form to vertex form is completing the square. This method is a form of algebraic manipulation in which we add and subtract a prescribed number to force the existence of a perfect square to factor. The following steps describe the process.

- Factor out the leading coefficient, \(a,\) in \(ax^2 + bx + c.\)

- Add and subtract the square of half the coefficient of the \(x\)-term,

- Factor the perfect square to obtain the form \(a(x - h)^2 + k.\)

- \(y = x^2 - 5x + 6\)

- \(y = -2x^2 - 8x + 11\)

- \(y = 3x^2 - 7x + 5\)

- With \(a = 1,\) there is no need to factor out a leading coefficient. The coefficient of the \(x\)-term is \(-5,\) half of which is \(-5/2.\) Thus, we add and subtract \((-5/2)^2 = 25/4\) to force the existence of the perfect square \(\left(x - \frac{5}{2} \right)^2 \col\) \[ \ba y &= x^2 - 5x + 6 \nl &= x^2 - 5x + \underline{\frac{25}{4}} - \underline{\frac{25}{4}} + 6 \nl &= \left(x - \frac{5}{2}\right)^2 + 6 -\frac{25}{4} \nl &= \boxed{\left(x - \frac{5}{2}\right)^2 - \frac{1}{4}} \ea \]

- Factoring out the leading coefficient \((-2)\) shows \[y = -2 \left(x^2 + 4x - \frac{11}{2} \right) \pd\] The coefficient of the \(x\) term is \(4,\) half of which is \(2.\) Then \(2^2 = 4.\) Accordingly, we add and subtract \(4\) in the parentheses: \[ \ba y &= -2 \left(x^2 + 4x + \underline{4} - \underline{4} - \frac{11}{2}\right) \nl &= -2(x + 2)^2 - 2 \left(-4 - \frac{11}{2}\right) \nl &= \boxed{-2(x + 2)^2 + 19} \ea \]

- First factoring out the leading coefficient \((3)\) gives \[y = 3 \left(x^2 - \frac{7}{3} x + \frac{5}{3}\right) \pd\] The coefficient of the \(x\)-term is \(-7/3.\) Half of the coefficient is \(-7/6,\) whose square is \(49/36.\) Thus, in the parentheses we add and subtract \(49/36 \col\) \[ \ba y &= 3 \left(x^2 - \frac{7}{3} x + \underline{\frac{49}{36}} - \underline{\frac{49}{36}} + \frac{5}{3} \right) \nl &= 3 \left(x - \frac{7}{6} \right)^2 + 3 \left(\frac{5}{3} - \frac{49}{36} \right) \nl &= \boxed{3 \left(x - \frac{7}{6} \right)^2 + \frac{11}{12}} \ea \]

Quadratic Formula and Discriminant

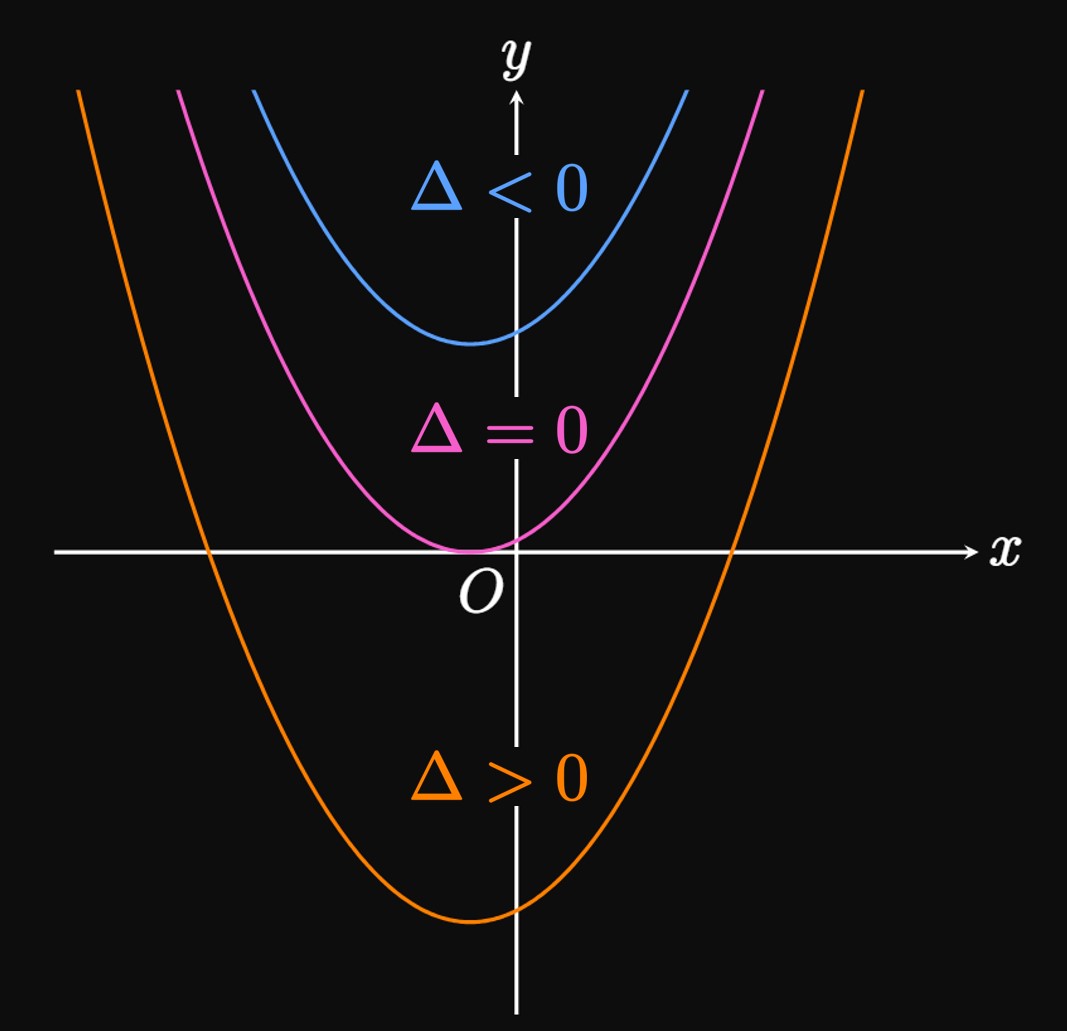

To solve the quadratic equation \(ax^2 + bx + c = 0,\) the first method we try is factoring. But when the expression cannot be factored, the Quadratic Formula is useful. It gives the general solution \begin{equation} x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} \pd \label{eq:quad-form} \end{equation} A quadratic equation may have two, one, or no real solutions, depending on the sign of the discriminant, \(\Delta = b^2 - 4ac,\) the expression in the square root of the quadratic formula:

- If \(\Delta \gt 0,\) then the equation has two real solutions.

- If \(\Delta = 0,\) then the equation has one real solution.

- If \(\Delta \lt 0,\) then the equation has no real solutions.

Figure 3 shows three parabolas. The top parabola never touches the \(x\)-axis, so its discriminant \(\Delta\) is negative because \(f(x) = 0\) has no real solutions. Conversely, the middle parabola only touches the \(x\)-axis once, so its discriminant \(\Delta\) is \(0.\) Lastly, the bottom parabola touches the \(x\)-axis twice, so its discriminant \(\Delta\) is positive.

- If \(\Delta \gt 0,\) then the equation has two real solutions.

- If \(\Delta = 0,\) then the equation has one real solution.

- If \(\Delta \lt 0,\) then the equation has no real solutions.

| Interval of \(x\) | Sign of \(4x^2 + 5x - 2\) |

| \(\ds \par{-\infty, \frac{-5 - \sqrt{57}}{8}}\) | \(+\) |

| \(\ds \par{\frac{-5 - \sqrt{57}}{8} \cma \frac{-5 + \sqrt{57}}{8}}\) | \(-\) |

| \(\ds \par{\frac{-5 + \sqrt{57}}{8} \cma \infty}\) | \(+\) |

Graphs of Quadratic Functions A quadratic expression is a second-degree polynomial. Its graph is a parabola, a symmetrical U-shaped curve. A quadratic function can be written in three canonical forms:

- The general form is \begin{equation} f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c \cma \eqlabel{eq:standard-form} \end{equation} where \((0, c)\) is the \(y\)-intercept of the parabola.

- The intercept form is \begin{equation} f(x) = a(x - p)(x - q) \cma \eqlabel{eq:intercept-form} \end{equation} where \(p\) and \(q\) are the zeros of \(y = f(x).\)

- The vertex form is \begin{equation} f(x) = a(x - h)^2 + k \cma \eqlabel{eq:vertex-form} \end{equation} where \((h, k)\) is the vertex, the lowest or highest point on the parabola, and the axis of symmetry is \(x = h,\) where \(h = -b/2a.\)

If \(a \gt 0,\) then the parabola opens upward; if \(a \lt 0,\) then the parabola opens downward.

Completing the Square One method to convert a quadratic function from general form \(ax^2 + bx + c\) to vertex form \(a(x - h)^2 + k\) is completing the square, whose steps are given as follows:

- Factor out the leading coefficient, \(a,\) in \(ax^2 + bx + c.\)

- Add and subtract the square of half the coefficient of the \(x\)-term,

- Factor the perfect square to obtain the form \(a(x - h)^2 + k.\)

Quadratic Formula and Discriminant Any quadratic equation \(ax^2 + bx + c = 0\) has solutions given by the Quadratic Formula: \begin{equation} x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} \pd \eqlabel{eq:quad-form} \end{equation} for nonzero \(a.\) The discriminant is the expression inside the square root, \(\Delta = b^2 - 4ac.\) The sign of \(\Delta\) indicates the number of real solutions to the quadratic equation:

- If \(\Delta \gt 0,\) then the equation has two real solutions.

- If \(\Delta = 0,\) then the equation has one real solution.

- If \(\Delta \lt 0,\) then the equation has no real solutions.