1.6: Limits with Infinity

This section expands our abilities with limits: We see what happens to a function as we let its input go toward \(\infty\) or \(-\infty.\) We also provide discussions of asymptotes and how they relate to infinity. This section discusses the following topics:

Let's immediately begin by distinguishing terminology: A limit at infinity is the behavior of a function \(f(x)\) as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty.\) A limit is infinite if \(f(x) \to \infty\) or \(f(x) \to -\infty\) as \(x\) approaches some value or changes without bound. When we say a limit equals infinity, it is implied that the limit does not exist; we are elaborating on how it fails to exist. Doing so is useful since it expands our toolkit for modeling functions' behaviors.

The expression \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L\) means that as \(x\) increases without bound,

\(f(x)\) is made closer and closer to \(L.\)

We can read the statement as the limit of \(f(x),\) as \(x\) approaches infinity, is \(L.\)

Likewise, \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L\) means that \(f(x)\) is made closer and closer to \(L\)

as \(x\) decreases without bound.

At the end of this section, we provide formal definitions for limits at infinity

and infinite limits.

Limits at Infinity

In Section 1.1 we briefly discussed limits at infinity of common functions. We asserted that for any positive integer \(k,\) \begin{flalign} &&\lim_{x \to \infty} x^k &= \infty \label{eq:lim-x^k} &\nl \laWord{and} &&\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{x^k} &= 0 \pd \label{eq:lim-1/x^k} \end{flalign} Similar to \(\eqref{eq:lim-1/x^k},\) if \(n\) is a positive integer, then \begin{equation} \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{1}{x^n} = 0 \pd \label{eq:lim-1/x^k-negative} \end{equation} These fundamentals allow us to solve more complicated limits at infinity.

Consider the family of limits

\begin{equation*}

L = \lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \cmaa g(x) \ne 0 \pd

\end{equation*}

If both \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) tend to \(\pm \infty\)

as \(x\) approaches \(a,\)

then \(L\) is of the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\)

For the specific case of

\[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \infty \and \lim_{x \to \infty} g(x) = \infty \cma\]

the ratio \(f(x)/g(x)\) symbolizes a battle:

As \(f\) increases, it tries to force the value of \(f/g\) toward infinity.

Yet as \(g\) grows, the denominator of \(f/g\) increases,

so the fraction's value is pushed down to \(0.\)

The result of this tug of war

is different each time,

so we cannot universalize the result of \(\indInfty.\)

As an example, the limit

\[\lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{x^2 + 4x}{x - 3}\]

is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty\)

since both the numerator and denominator approach \(\infty\) as \(x \to \infty.\)

The limit therefore cannot be evaluated using Direct Substitution,

nor can its value be inferred from \(\eqref{eq:lim-1/x^k}.\)

Limits of rational functions at infinity are often in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) The following example demonstrates the strategy for resolving them.

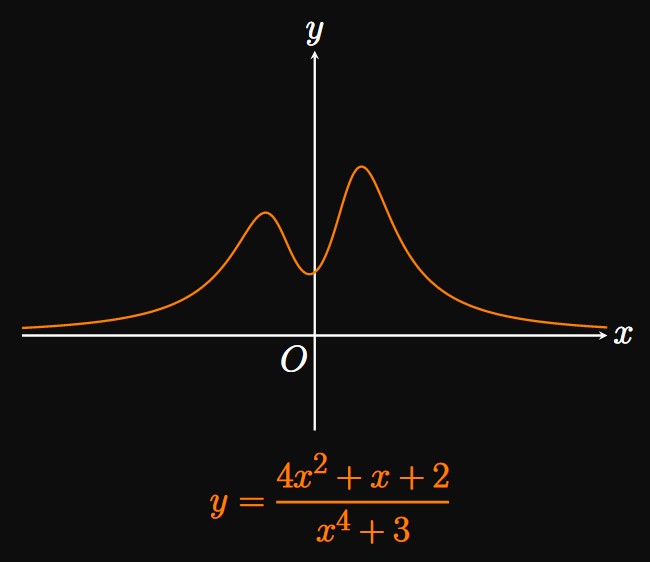

As \(x\) increases without bound, the numerator and denominator also grow indefinitely. Consequently, as \(x \to \infty\) \[4x^2 + x + 2 \to \infty \and x^4 + 3 \to \infty \pd\] Hence, \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x)\) is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) There are two strategies for finding this limit.

Method 1 Let's divide the numerator and denominator each by the highest-degree term in the denominator—namely, \(x^4.\) Doing so shows \[ \baat{2} \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{4x^2 + x + 2}{x^4 + 3} &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{4x^2 + x + 2}{x^4 + 3} \cdot \frac{1/x^4}{1/x^4} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{4/x^2 + 1/x^3 + 2/x^4}{1 + 3/x^4} \nl &= \frac{\ds \lim_{x \to \infty} \par{4/x^2 + 1/x^3 + 2/x^4}}{\ds \lim_{x \to \infty} \par{1 + 3/x^4}} \comment{\text{by Quotient Law}} \nl &= \frac{0 + 0 + 0}{1 + 0} \comment{\text{by } \eqref{eq:lim-1/x^k}} \nl &= \boxed 0 \eaat \] (See Figure 1.)

Method 2 There is a shortcut: As \(x\) grows infinitely large, the highest-degree terms in the numerator and denominator are the most significant. Thus, all the lower-degree terms can be neglected. Accordingly, as \(x\) grows to infinity, the behavior of \(f(x)\) matches the behavior of \(4x^2/x^4 = 4/x^2.\) Therefore, \[ \ba \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{4x^2 + x + 2}{x^4 + 3} &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{4x^2}{x^4} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{4}{x^2} \nl &= \boxed 0 \ea \]

We generalize the strategies in Example 1 for limits of rational functions, as follows.

- Method 1 Divide all the terms by the highest-degree term in the denominator.

- Method 2 Take the limit of only the highest-degree terms in the numerator and denominator.

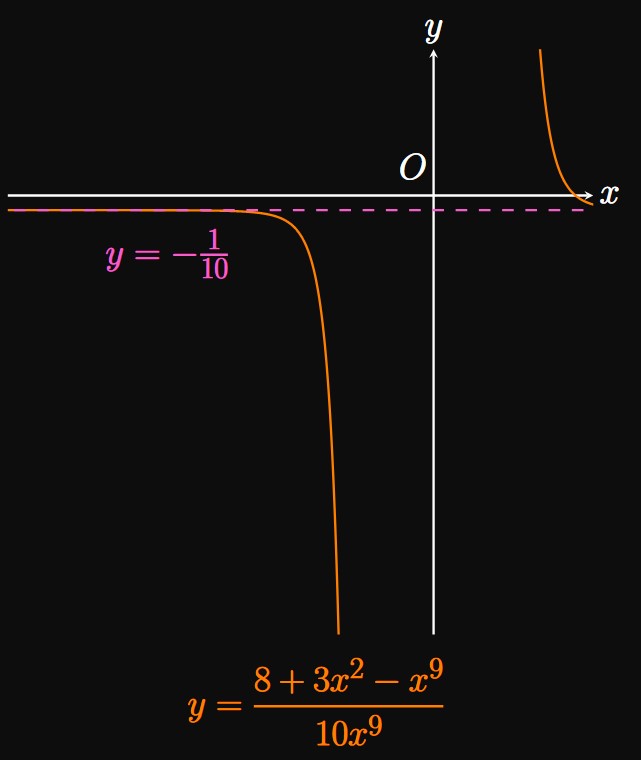

Method 1 The highest-degree term in the denominator is \(x^9.\) Dividing all the terms by \(x^9,\) we see \[ \baat{2} \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{8 + 3x^2 - x^9}{10x^9} &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{8 + 3x^2 - x^9}{10x^9} \cdot \frac{1/x^9}{1/x^9} \nl &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{8/x^9 + 3/x^7 - 1}{10} \nl &= \frac{\ds \lim_{x \to -\infty} \par{8/x^9 + 3/x^7 - 1}}{\ds \lim_{x \to -\infty} 10} \comment{\text{by Quotient Law}} \nl &= \frac{0 + 0 - 1}{10} \comment{\text{by } \eqref{eq:lim-1/x^k}} \nl &= \boxed{-\frac{1}{10}} \eaat \] (See Figure 2.)

Method 2 The highest-degree terms in the numerator and denominator dominate the limit. Therefore, \[ \ba \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{8 + 3x^2 - x^9}{10x^9} &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{-x^9}{10x^9} \nl &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{-1}{10} \nl &= \boxed{-\frac{1}{10}} \ea \]

Asymptotes; End Behavior

A function's end behavior describes its behavior at infinity and negative infinity, which we investigate by considering the limits \[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) \and \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) \pd\] If both limits exist, then as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty\) the graph of \(y = f(x)\) approaches a horizontal line. In particular, the graph has a horizontal asymptote of \(y = L\) if either \[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L \or \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L \pd\]

A function may have zero, one, or two horizontal asymptotes. Figure 3 shows the graph of a function \(f\) with one horizontal asymptote, \(y = L,\) so it satisfies \[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L \pd\] On the contrary, a function \(f\) has two horizontal asymptotes if \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x)\) and \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x)\) equal different values. An example is \(f(x) = \atan x,\) whose graph has horizontal asymptotes of \(y = -\pi/2\) and \(y = \pi/2\) (Figure 4). Lastly, the function \(f\) has no horizontal asymptotes if \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x)\) and \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x)\) both fail to exist (for example, both limits equal infinity). Non-constant polynomials have no horizontal asymptotes because they feature infinite limits at infinity.

To describe the end behavior of \(g,\) we need its limits at infinity: \[\lim_{x \to \infty} g(x) \and \lim_{x \to -\infty} g(x) \pd\]

Limits at Infinity Let's divide each term by the denominator's highest-degree term—namely, \(x^3.\) We see \[ \ba \lim_{x \to \infty} g(x) &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\sqrt{x^6 + x}}{5x^3 + 7} \cdot \frac{1/x^3}{1/x^3} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\ds {\small \frac{\sqrt{x^6 + x}}{x^3 \strut}} }{\ds 5 + 7/x^3} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\ds {\small \frac{\sqrt{x^6 + x}}{\sqrt{x^6} \strut}}}{\ds 5 + 7/x^3} \lspace \parbr{\sqrt{x^6} = x^3 \text{ for } x \gt 0} \nl &= \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\ds {\small \sqrt{\frac{x^6 + x}{\strut x^6}}}}{\ds 5 + 7/x^3} = \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{\ds \sqrt{{\small 1 + \frac{1}{x^5}}}}{\ds 5 + 7/x^3} \nl &= \frac{\ds \sqrt{\lim_{x \to \infty} \par{{\small 1 + \frac{1}{x^5}}}}}{\ds \lim_{x \to \infty} \par{5 + 7/x^3}} = \frac{\sqrt{1 + 0}}{5 + 0} = \boxed{\frac{1}{5}} \ea \] Conversely, in calculating the limit as \(x \to -\infty,\) we consider negative \(x.\) Then \(\sqrt{x^6}\) \(= \abs{x^3}\) \(= -x^3\) for \(x \lt 0.\) Hence, dividing the numerator of \(g(x)\) by \(x^3\) is equivalent to dividing by \(-\sqrt{x^6} \col\) \[\frac{\sqrt{x^6 + x}}{x^3} = \frac{\sqrt{x^6 + x}}{-\sqrt{x^6}} = -\sqrt{1 + \frac{1}{x^5}} \pd\] The remaining steps are similar to our procedure for evaluating \(\lim_{x \to \infty} g(x);\) using \(\eqref{eq:lim-1/x^k-negative},\) we see \[ \ba \lim_{x \to -\infty} g(x) &= \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{\ds -\sqrt{{\small 1 + \frac{1}{\strut x^5}}}}{\ds 5 + 7/x^3} \nl &= \frac{\ds -\sqrt{\lim_{x \to -\infty} {\small \par{1 + \frac{1}{\strut x^5}}} }}{\ds \lim_{x \to -\infty} \par{5 + 7/x^3}} \nl &= \frac{- \sqrt{1 + 0}}{5} = \boxed{-\frac{1}{5}} \ea \]

End Behavior We say \(g(x) \to 1/5\) as \(x \to \infty\) and \(g(x) \to -1/5\) as \(x \to -\infty.\) Because both limits exist, the horizontal asymptotes of \(g\) are \(y = 1/5\) and \(y = -1/5.\) (See Figure 5.)

Limits at Vertical Asymptotes

If a function \(f(x)\) has a vertical asymptote at \(x = p,\) then \(f\) approaches either \(\infty\) or \(-\infty\) on either side of the asymptote, as discussed in Section 1.1. Recall that a function has a vertical asymptote when the denominator equals \(0\) and the numerator is nonzero. Our goal is to establish whether a one-sided limit at a vertical asymptote equals \(\infty\) or \(-\infty.\) To do so, we consider a function's sign on either side of the vertical asymptote. If a function is large positive on one side of the vertical asymptote, then the one-sided limit equals \(\infty.\) Likewise, the one-sided limit equals \(-\infty\) if the function is large negative on that side of the vertical asymptote.

- If \(f(x) \lt 0\) as \(x \to p^-,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^-} f(x) = -\infty.\)

- If \(f(x) \gt 0\) as \(x \to p^-,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^-} f(x) = \infty.\)

- If \(f(x) \lt 0\) as \(x \to p^+,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^+} f(x) = -\infty.\)

- If \(f(x) \gt 0\) as \(x \to p^+,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^+} f(x) = \infty.\)

To find the horizontal asymptotes of \(f,\) we evaluate its limits at infinity: \[ \ba \lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) &= -\tfrac{2}{3} \cma \nl \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) &= - \tfrac{2}{3} \pd \ea \] Both limits are the same, so the graph of \(f\) has only one horizontal asymptote: \(\boxed{y = -2/3}.\)

A rational function has a vertical asymptote when its denominator is \(0\) while its numerator is nonzero. Equating the denominator of \(f(x)\) to \(0\) gives \(x = 8/3,\) at which the numerator is simultaneously nonzero. Thus, \(\boxed{x = 8/3}\) is the only vertical asymptote of \(f.\) (See Figure 6.)

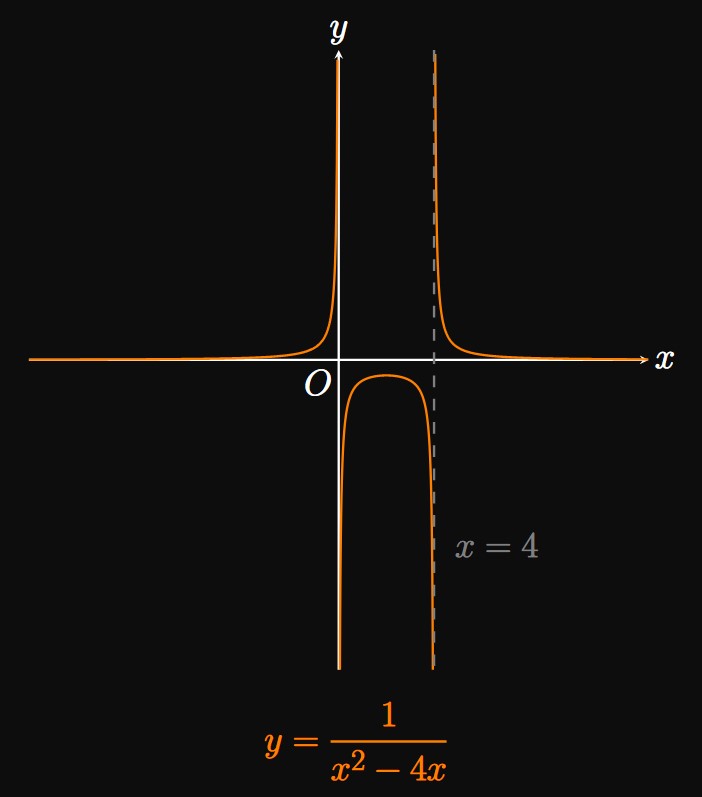

The graph has no \(x\)-intercepts since \(1/(x^2 - 4x)\) never equals \(0.\) The graph also lacks a \(y\)-intercept because the function is undefined at \(x = 0.\) Factoring the denominator gives \[f(x) = \frac{1}{x(x - 4)} \pd\] The graph of \(y = f(x)\) has vertical asymptotes at \(x = 0\) and \(x = 4\) because at each \(x,\) the denominator equals \(0\) while the numerator is nonzero.

The following table shows the sign of \(f\) on intervals bounded between \(x = 0\) and \(x = 4.\)

| Interval of \(x\) | \(x\) | \((x - 4)\) | \(\ds f(x) = \frac{1}{x(x - 4)}\) |

| \(x \lt 0\) | \(-\) | \(-\) | \(+\) |

| \(0 \lt x \lt 4\) | \(+\) | \(-\) | \(-\) |

| \(x \gt 4\) | \(+\) | \(+\) | \(+\) |

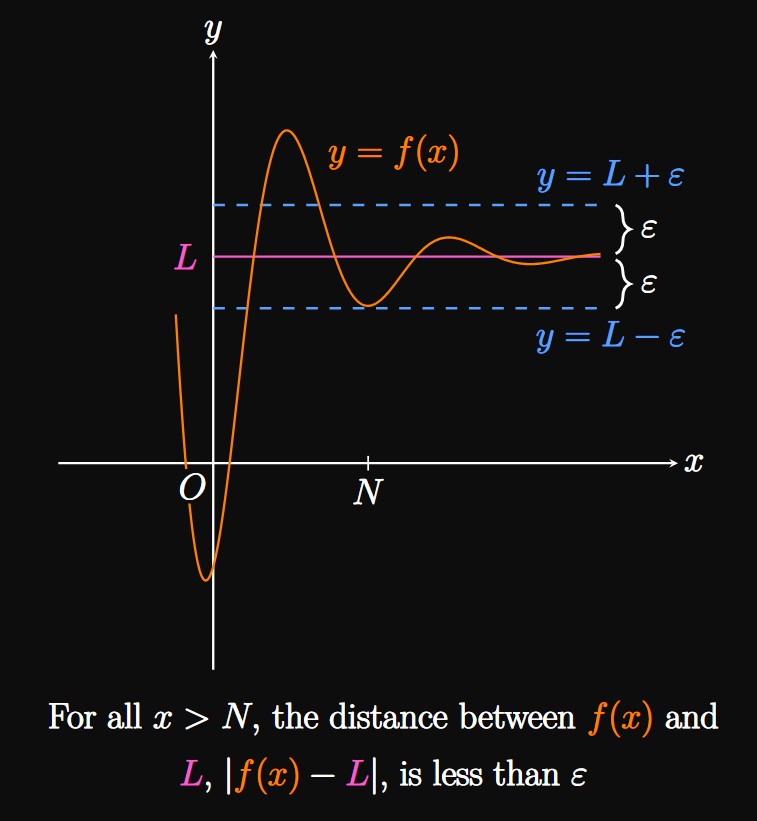

Formal Definitions of Limits with Infinity

Finite Limits at Infinity Let \(f(x)\) be a function defined over some interval \(x \geq a.\) The statement \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L\) means that \(f(x)\) can be made as close to \(L\) as we want by making \(x\) sufficiently large. The precise definition is as follows: For all positive numbers \(\varepsilon,\) a number \(N\) exists such that if \(x \gt N,\) then the distance between \(f(x)\) and \(L\) is less than \(\varepsilon.\) In other words, \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L\) if and only if \[\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \for x \gt N \pd\] See Figure 6: The region between \(L - \varepsilon\) and \(L + \varepsilon\) represents the values of \(f(x)\) within \(\varepsilon\) of \(L.\) If we wish to make the bound \(\varepsilon\) smaller, then \(N\) must be made bigger. Likewise, \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L\) means that for \(\varepsilon \gt 0,\) \[\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \for x \lt N \pd\]

When we construct proofs of limits at infinity, our objective is to find \(N\) such that \(\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon.\) Typically, we express \(N\) in terms of \(\varepsilon.\) Doing so gives us the freedom to choose any positive bound \(\varepsilon\)—making the function \(f\) arbitrarily close to the limit \(L\) for \(x \gt N.\)

- \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \for x \gt N \pd\]

- \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \for x \lt N \pd\]

Infinite Limits at Infinity Let \(f(x)\) be a function defined over an interval \(x \geq a.\) Suppose \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \infty;\) in words, this statement says that \(f\) increases without bound as \(x\) is made arbitrarily large. Thus, we say that \(f\) is always greater than a given value \(M\) when \(x\) is large—say, for \(x \gt N.\) You can think of \(N\) as a lower bound for the values of \(x\) that ensure \(f(x) \gt M.\) (See Figure 8.) So \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if \[f(x) \gt M \for x \gt N \pd\] In this statement, if we wish to increase \(M,\) then \(N\) must increase accordingly. Similarly, \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if \(f\) is always greater than some number \(M \col\) \[f(x) \gt M \for x \lt N \pd\] The number \(N\) is an upper bound for \(x\) such that \(f(x) \gt M.\)

- \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[f(x) \gt M \for x \gt N \pd\]

- \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[f(x) \gt M \for x \lt N \pd\]

Limits at Infinity A limit at infinity is the behavior of a function \(f(x)\) as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty.\) The following three limits at infinity are foundational: \begin{align} \lim_{x \to \infty} x^k &= \infty \cma \eqlabel{eq:lim-x^k} \nl \lim_{x \to \infty} \frac{1}{x^k} &= 0 \cma \eqlabel{eq:lim-1/x^k} \nl \lim_{x \to -\infty} \frac{1}{x^n} &= 0 \cma \eqlabel{eq:lim-1/x^k-negative} \end{align} where \(k\) is a positive constant and \(n\) is a positive integer. Consider the limit \[L = \lim_{x \to a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} \cmaa g(x) \ne 0 \pd\] If both \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) approach \(\pm \infty\) as \(x\) approaches \(a,\) then the limit is in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty,\) meaning Direct Substitution yields an inconclusive result. Limits of rational functions as \(x \to \infty\) are very commonly in the indeterminate form \(\indInfty.\) To evaluate these limits, divide every term by the highest-degree term in the denominator. Alternatively, you can take the limit of only the highest-degree terms in the numerator and denominator, neglecting the other terms.

Asymptotes; End Behavior The end behavior of a function \(f\) describes the graph's behavior at infinity and negative infinity. We consider end behavior by evaluating \[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) \and \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) \pd\] If either limit exists, then the graph has a horizontal asymptote—a horizontal line that \(y = f(x)\) approaches as \(x\) becomes unbounded. The graph has a horizontal asymptote of \(y = L\) if either \[\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L \or \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L \pd\] A function may have zero, one, or two horizontal asymptotes. To find the behavior of a function \(f(x)\) at a vertical asymptote \(x = p,\) we analyze the sign of \(f\) on either side of the asymptote:

- If \(f(x) \lt 0\) as \(x \to p^-,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^-} f(x) = -\infty.\)

- If \(f(x) \gt 0\) as \(x \to p^-,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^-} f(x) = \infty.\)

- If \(f(x) \lt 0\) as \(x \to p^+,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^+} f(x) = -\infty.\)

- If \(f(x) \gt 0\) as \(x \to p^+,\) then \(\lim_{x \to p^+} f(x) = \infty.\)

Formal Definitions of Limits with Infinity When we write proofs for finite limits at infinity, we assert that a function \(f(x)\) is confined to a value \(L\) as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty.\) Let \(\varepsilon\) be any positive number.

- \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \for x \gt N \pd\]

- \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = L\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[\abs{f(x) - L} \lt \varepsilon \for x \lt N \pd\]

For infinite limits at infinity, we show that a function \(f(x)\) changes without bound as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty.\) Let \(M\) be any positive number.

- \(\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[f(x) \gt M \for x \gt N \pd\]

- \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) = \infty\) if and only if there exists a number \(N\) such that \[f(x) \gt M \for x \lt N \pd\]