3.2: Mean Value Theorem and Rolle's Theorem

In Section 2.1 we defined a function's instantaneous rate of change, which we contrasted with its average rate of change over an interval. Although they are different, a connection exists between these two concepts, which we explore through the following topics:

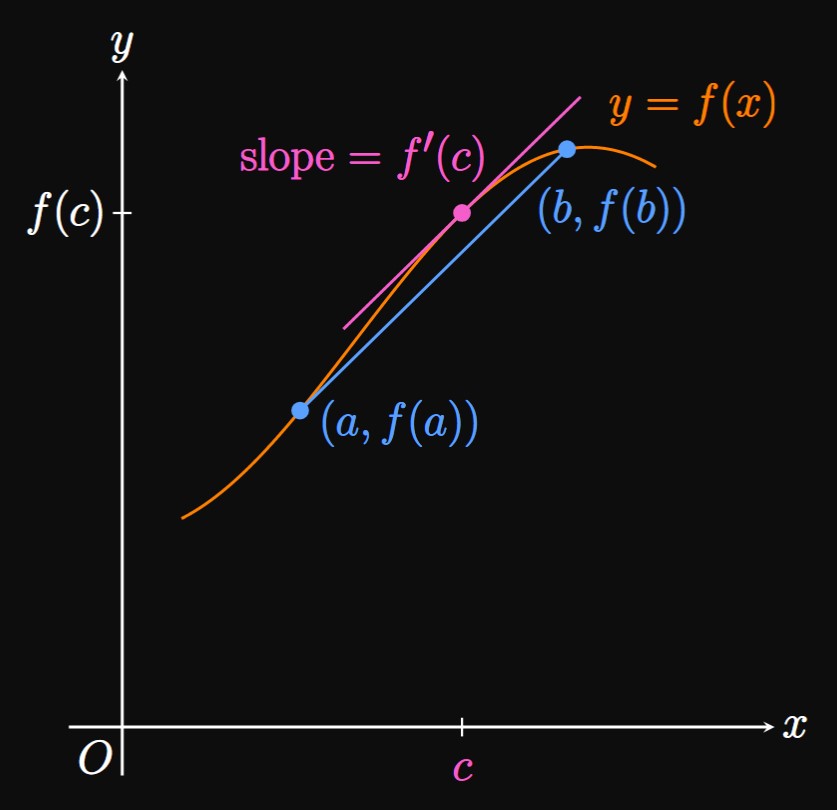

Reviewing Types of Change The average rate of change of a function \(f\) over the interval \([a, b]\) is \[\frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x} = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} \pd\] This ratio represents the slope of the secant line to the graph of \(y = f(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = b\) (Figure 1A). In contrast, the instantaneous rate of change of \(f(x)\) at \(x = c\) is \(f'(c),\) the slope of the tangent line to \(y = f(x)\) at \(x = c\) (Figure 1B). We will use these definitions extensively in this section.

Rolle's Theorem

This section centers on a single mathematical principle, the Mean Value Theorem. To arrive at this theorem, we first bridge the gap by defining Rolle's Theorem, as discussed below.

- \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b].\)

- \(f\) is differentiable on \((a, b).\)

- \(f(a) = f(b).\)

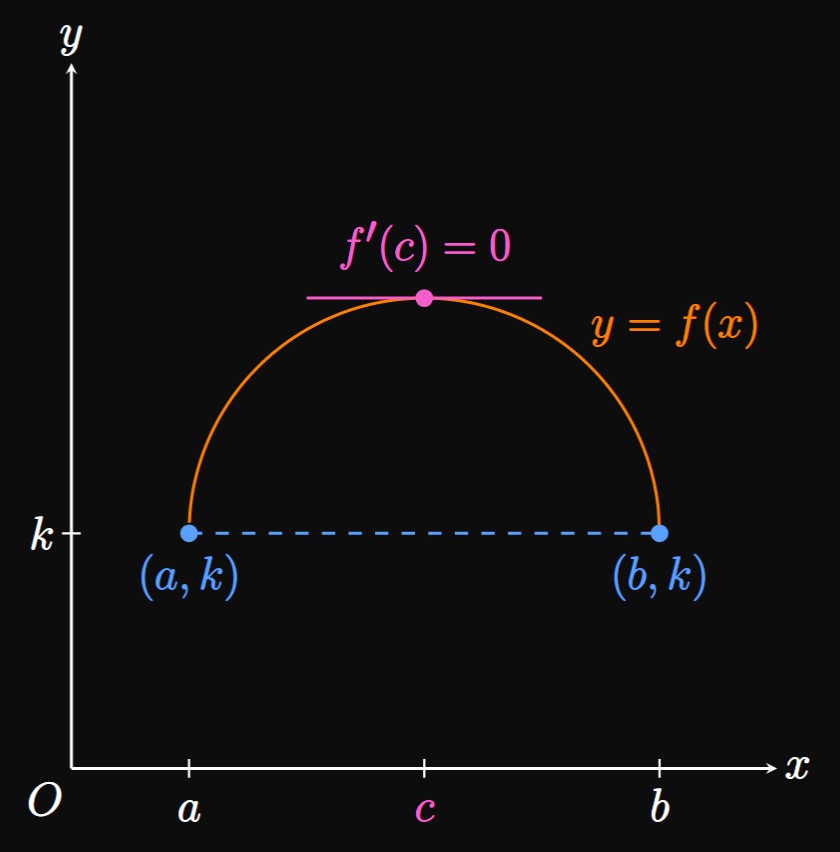

Visually, the graph of a function \(y = f(x)\) is shown in Figure 2. We see that \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b]\) and differentiable on \((a, b).\) Moreover, \(f(a) = f(b) = k,\) so the average rate of change of \(f\) on \([a, b]\) is \[\frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} = \frac{k - k}{b - a} = 0 \pd\] Accordingly, the secant line connecting the points \((a, k)\) and \((b, k)\) is horizontal. Rolle's Theorem guarantees a number \(c\) in \((a, b)\) such that \(f'(c) = 0,\) meaning the graph of \(f\) has a horizontal tangent at \(x = c.\) In words, the theorem asserts that the graph must have at least one horizontal tangent at some point between \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\)

PROOF We divide the proof into three cases.

- Case 1, \(f(x) = k,\) a constant Since \(f'(x) = 0,\) \(c\) can be any number in \((a, b).\)

- Case 2, \(f(x) \gt f(a)\) for some \(x\) in \((a, b)\) Because \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b],\) the Extreme Value Theorem guarantees a maximum value in \([a, b].\) Yet \(f(a) = f(b),\) so the maximum value must be at some number \(c\) in the open interval \((a, b).\) Accordingly, \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(c.\) (This case is shown in Figure 2.) Since \(f\) is differentiable at \(c,\) Fermat's Theorem gives \(f'(c) = 0.\)

- Case 3, \(f(x) \lt f(a)\) for some \(x\) in \((a, b)\) Similarly to case 2, the Extreme Value Theorem guarantees a minimum value in \([a, b].\) Again, \(f(a) = f(b),\) so \(f\) attains its minimum at some \(c\) in the open interval \((a, b).\) Hence, \(f'(c) = 0\) by Fermat's Theorem.

By using a Proof by Contradiction, Rolle's Theorem can be used to prove that a function only has one zero. The following example provides a walkthrough of this process.

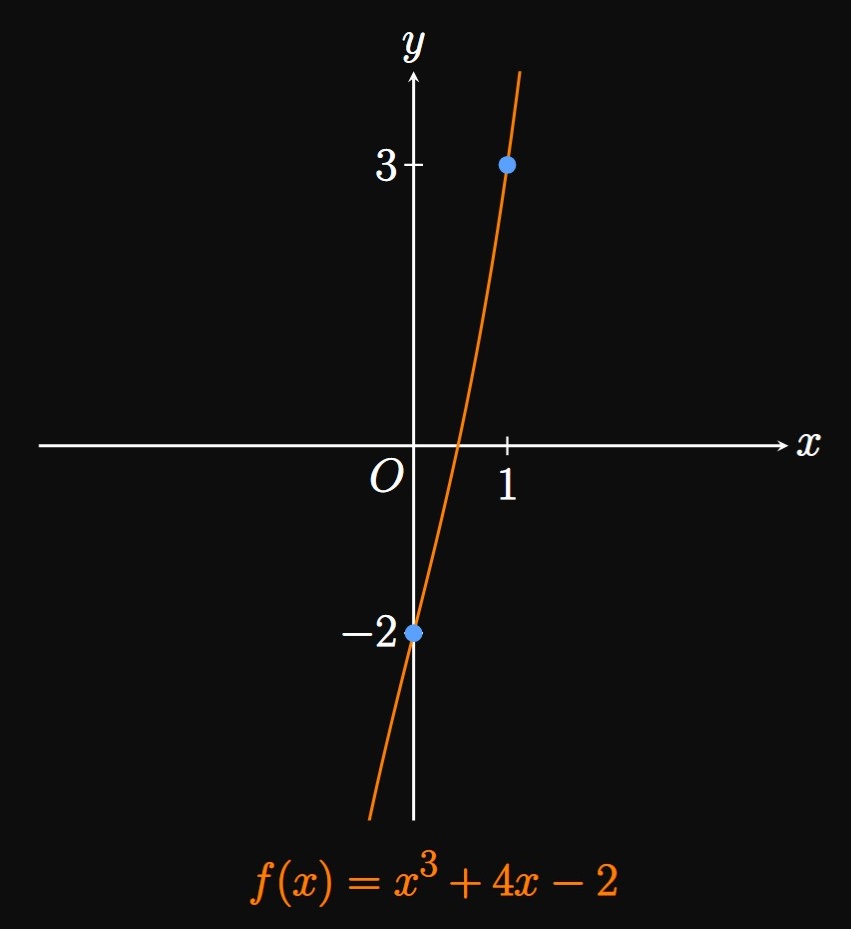

Note that \(f(0) = -2\) and \(f(1) = 3.\) Since \(f\) is a polynomial, it is continuous on \(\RR.\) By the Intermediate Value Theorem (from Section 1.4), \(f(x) = 0\) has a solution between \(x = 0\) and \(x = 1.\) Now we prove that \(f\) has no other zeros.

Proof by Contradiction Let's assume \(f\) has two roots, \(a\) and \(b.\) Then \(f(a) = f(b) = 0.\) In addition, \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b]\) and differentiable on \((a, b)\) since it's a polynomial. Rolle's Theorem says a value \(c\) exists between \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(f'(c) = 0.\) Yet \[f'(x) = 3x^2 + 4 \cma\] which is strictly positive. Thus, \(f'(c) = 0\) has no solutions, so no value of \(c\) satisfies Rolle's Theorem. We have a contradiction—\(f\) cannot have two zeros. The graph of \(y = f(x)\) is shown in Figure 5, which corroborates this conclusion.

Mean Value Theorem

Let \(f\) be a function that is continuous on \([a, b]\) and differentiable on \((a, b).\) Its average rate of change on \([a, b]\) is \[\frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x} = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} \pd \] The Mean Value Theorem then guarantees a value \(c\) in \((a, b)\) such that \[f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} \pd \] In words, there is at least one point \((c, f(c))\) on the graph at which the tangent's slope equals the slope of the secant line between \((a, f(a))\) and \((b, f(b)).\) Then the tangent line at \(c\) is parallel to the secant line. (See Figure 6.)

The Mean Value Theorem may be satisfied for \(f\) by several values of \(c\) in \((a, b),\) similarly to the existence of multiple \(c\) values in Example 2. In other words, the graph of \(y = f(x)\) may have several tangent lines that are parallel to the secant line between \((a, f(a))\) and \((b, f(b)).\)

Note that the Mean Value Theorem's continuity and differentiability requirements are identical to those for Rolle's Theorem. In fact, Rolle's Theorem is a special case of the Mean Value Theorem for an average rate of change of \(0.\)

PROOF

Let \(f\) be continuous on \([a, b]\) and differentiable on \((a, b).\)

Consider two points, \(A(a, f(a))\) and \(B(b, f(b)).\)

By the point-slope form of a line, an equation of line \(AB\) is

\[

y - f(a) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} (x - a) \pd

\]

Solving for \(y\) gives

\[y = f(a) + \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} (x - a) \pd\]

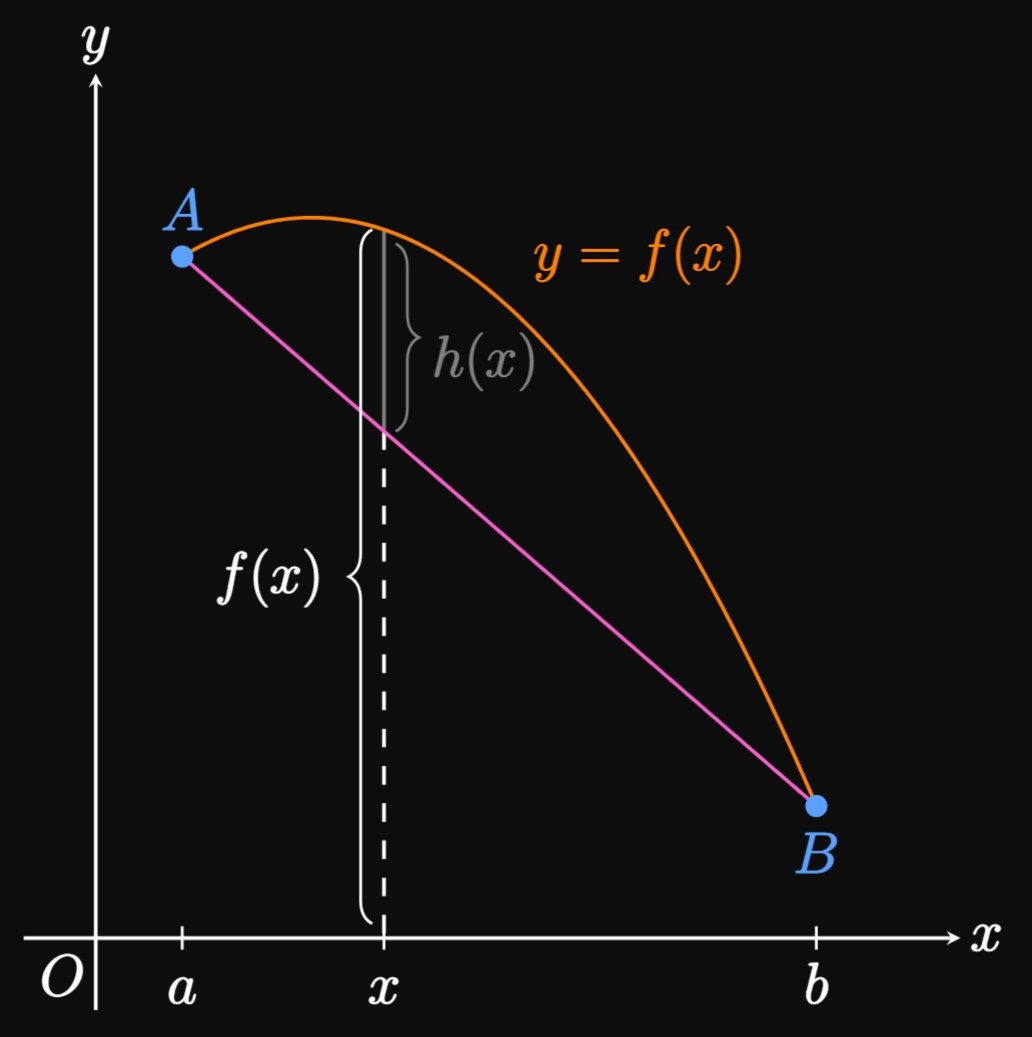

We define a new function \(h(x)\) as the difference between \(f(x)\) and the secant line, \(AB.\)

[See Figure 7 for the special case

where \(f\) is greater than its secant line on

- Function \(h\) is continuous on \([a, b]\) since it's the sum of \(f\) and a first-degree polynomial, which are both continuous.

- Function \(h\) is differentiable on \((a, b)\) because both \(f\) and the first-degree polynomial are differentiable.

- By \(\eqref{eq:h(x)-def},\) \[ \ba h(a) &= f(a) - f(a) - \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} (a - a) \nl &= 0 \pd \ea \] Likewise, \[ \ba h(b) &= f(b) - f(a) - \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} (b - a) \nl &= f(b) - f(a) - [f(b) - f(a)] \nl &= 0 \pd \ea \] Thus, \(h(a) = h(b).\)

- the largest possible value of \(f(5)\)

- the smallest possible value of \(f(5)\)

- Because \(2 \leq f'(x) \leq 4,\) the maximum value of \(f'(x)\)—and, consequently, of \(f'(c)\)—is \(4.\) Accordingly, the maximum possible value of \(f(5)\) is, by \(\eqref{eq:mvt-ex},\) \[f(5) = 2 + 4(4) = \boxed{18}\]

- The minimum value of \(f'(c)\) is \(2,\) so by \(\eqref{eq:mvt-ex}\) the minimum possible value of \(f(5)\) is \[f(5) = 2 + 4(2) = \boxed{10}\]

Average Velocities If an object moves in a straight line with position function \(s(t),\) then its average velocity between \(t = a\) and \(t = b\) is \[\avg v = \frac{s(b) - s(a)}{b - a} \pd\] Because real-world movement is smooth, we take \(s\) to be continuous on \([a,b]\) and differentiable on \((a, b).\) Accordingly, the Mean Value Theorem guarantees that the object's instantaneous velocity equals \(\avg v\) at some \(t = c\) between \(t = a\) and \(t = b.\) The Mean Value Theorem can therefore be used to convict speeding drivers. For example, a driver who travels \(140\) miles in two hours has an average speed of \[\avg v = \frac{140}{2} = 70 \un{mph} \pd\] Thus, the Mean Value Theorem proves that the speedometer must have read \(70 \un{mph}\) at least once in the driver's journey.

- Find the average rate of change of \(f\) on \([0, 4].\) Must there be a value \(c\) in \((0, 4)\) such that \(f'(c)\) equals this average rate of change?

- Does \(f\) satisfy Rolle's Theorem on \([-4, 4] \ques\)

- We see \(f(0) = 4\) and \(f(4) = 0.\) Thus, the average rate of change is \[\frac{f(4) - f(0)}{4 - 0} = \frac{0 - 4}{4 - 0} = \boxed{-1}\] Since \(f\) is continuous on \([0, 4]\) and differentiable on \((0, 4),\) the Mean Value Theorem indeed guarantees a value \(c\) in \((0, 4)\) such that \(f'(c) = -1.\)

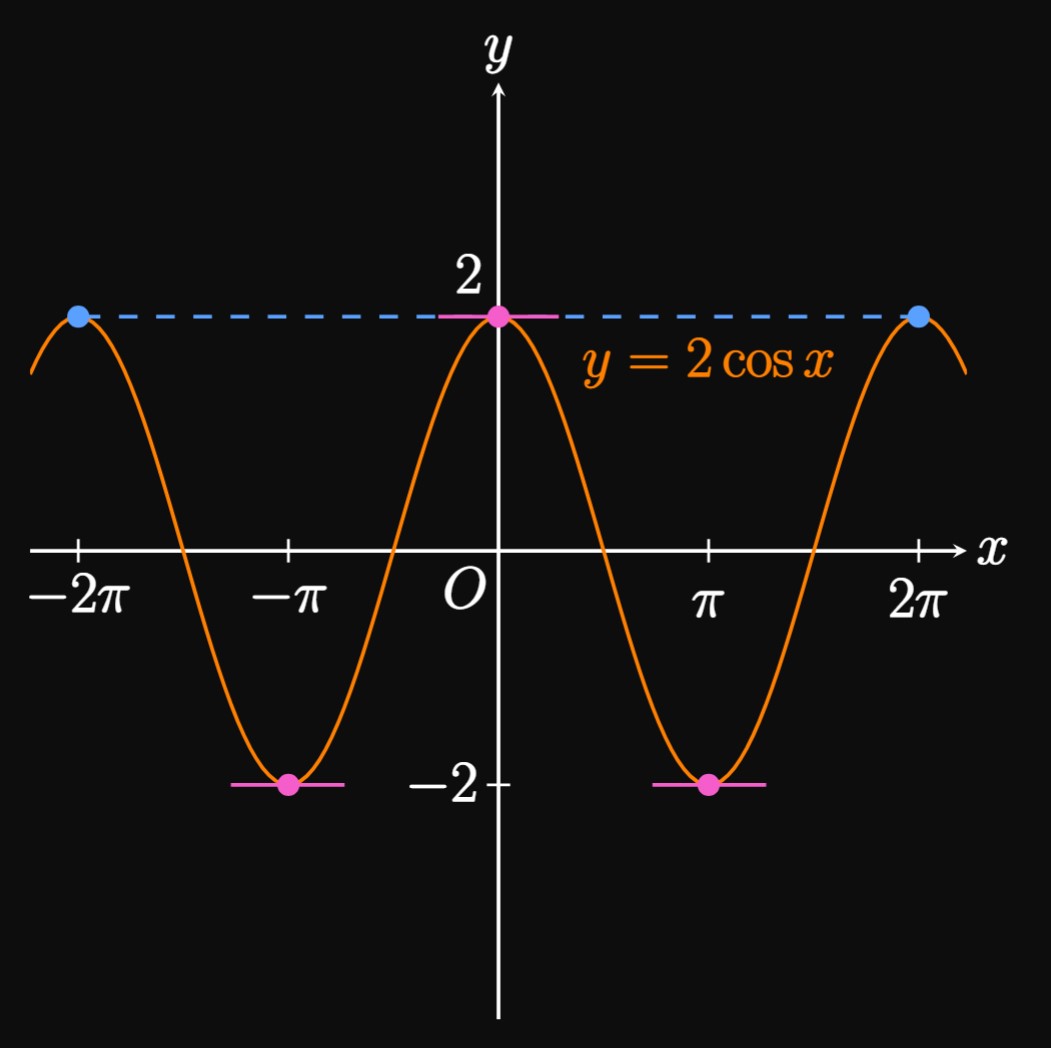

- The average rate of change of \(f\) on \([-4, 4]\) is \[\frac{f(4) - f(-4)}{4 - (-4)} = \frac{0 - 0}{8} = 0 \pd\] But \(f\) does not meet the conditions of Rolle's Theorem: the graph has a sharp turn at \(x = 0,\) so \(f\) is not differentiable on \((-4, 4).\)

Rolle's Theorem Suppose function \(f\) satisfies the following conditions.

- \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b].\)

- \(f\) is differentiable on \((a, b).\)

- \(f(a) = f(b).\)

Then Rolle's Theorem guarantees a value \(c\) in \((a, b)\) such that \(f'(c) = 0.\) Geometrically, the theorem asserts that the graph of \(y = f(x)\) must have a horizontal tangent at some point between \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\) Through a Proof by Contradiction, we can use Rolle's Theorem to show that a function only has one zero.

Mean Value Theorem If \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b]\) and differentiable on \((a, b),\) then the Mean Value Theorem guarantees a value \(c\) in \((a, b)\) such that \[f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} \pd\] In words, this theorem guarantees at least one point in \(a \lt x \lt b\) such that the line tangent to the graph of \(y = f(x)\) is parallel to the secant line formed by \((a, f(a))\) and \((b, f(b)).\) Rolle's Theorem is a special case of the Mean Value Theorem for \(f(a) = f(b).\)