3.4: Particle Motion

As Isaac Newton developed calculus, one of his primary objectives was to model motion in physics. In Section 2.1 we used calculus to connect position, velocity and acceleration. Yet properties of first and second derivatives enable us to further analyze these contexts. In this section we study properties of particle motion: calculating when an object changes direction, how much distance it covers, and whether it is speeding up or slowing down.

Let's first review the fundamental terminology in particle motion. Suppose that a particle travels along a line with time \(t.\) Then its position (from a reference point) is given by some function of time, namely, \(s(t).\) If \(s_1\) is the particle's position at \(t = t_1\) and \(s_2\) is its position at some later time \(t = t_2,\) then the particle's displacement is \(\Delta s\) \(= s_2 - s_1.\) In words, displacement is the difference in a particle's position. (If you walk \(5\) units north and then \(4\) units south, then your displacement is \(1\) unit north.) Recall, from Section 2.1, that the velocity function is the time derivative of position: \[v(t) = \deriv{s}{t} \pd\] The acceleration function is the time derivative of velocity—namely, \[a(t) = \deriv{v}{t} = \derivOrder{s}{t}{2} \pd\] The axis along which the particle travels contains a positive direction and a negative direction. For example, if a particle moving to the right is defined to have a positive velocity, then its velocity becomes negative upon turning around and moving to the left. Speed is the absolute value of velocity, so we define a particle's speed function to be \[\abs{v(t)} = \abs{s'(t)} \pd\] Hence, velocity is the speed in a certain direction.

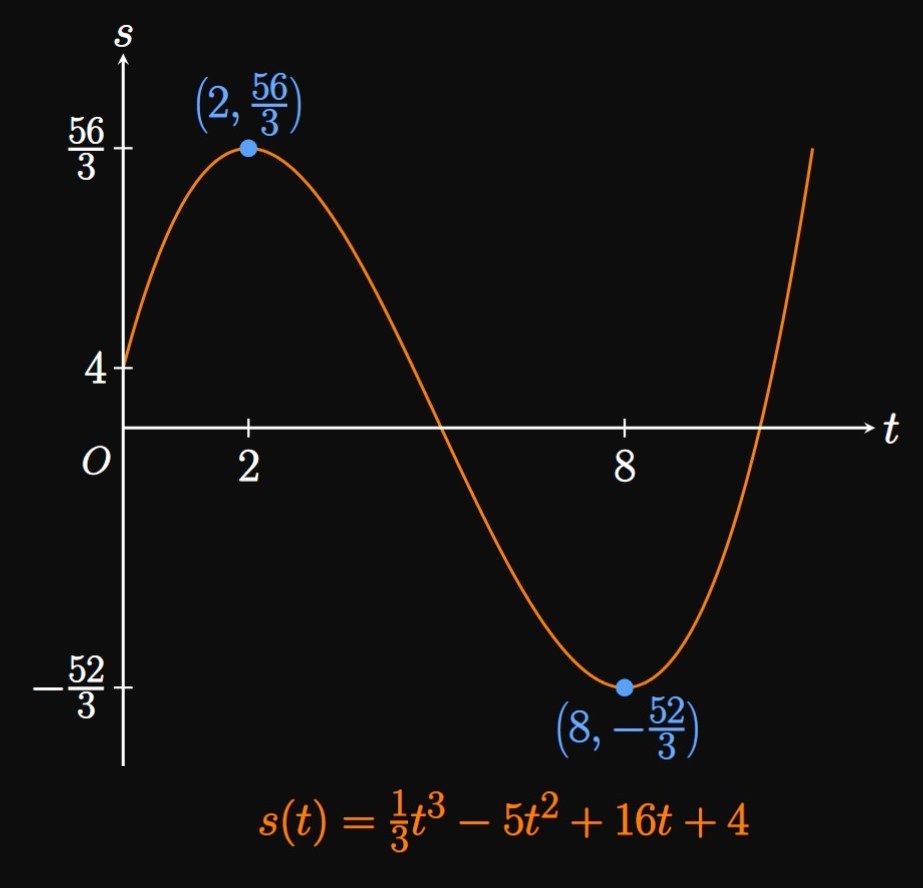

An object changes direction when its velocity function swaps sign. The First-Derivative Test (from Section 3.1) asserts that a function has relative extrema when its derivative function changes sign. Since \(s'(t)\) \(= v(t),\) the times at which a particle changes direction correspond to the relative extrema of \(s(t).\)

| Interval of \(t\) | \(v(t) = (t - 8)(t - 2)\) |

| \((0, 2)\) | \(+\) |

| \((2, 8)\) | \(-\) |

| \((8, \infty)\) | \(+\) |

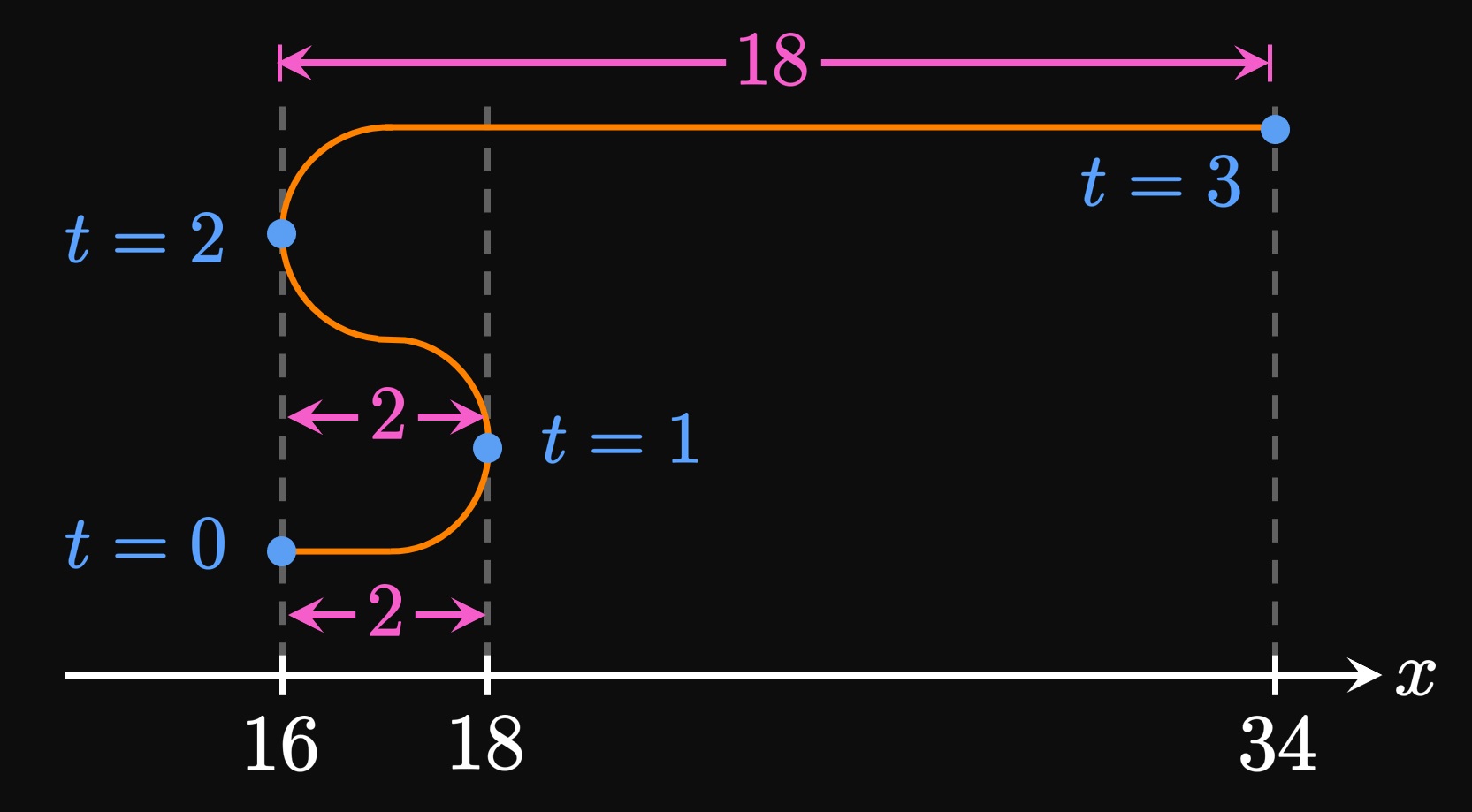

| Interval of \(t\) | \(v(t) = 8t (t - 2)(t - 1)\) | Displacement |

| \((0, 1)\) | \(+\) | \(x(1) - x(0) = 2\) |

| \((1, 2)\) | \(-\) | \(x(2) - x(1) = -2\) |

| \((2, 3)\) | \(+\) | \(x(3) - x(2) = 18\) |

When you step on the gas pedal, the car is propelled in the same direction it's facing, so you speed up. In contrast, by pressing the brake pedal, the car is pushed in the opposite direction and so you slow down. Thus, a particle is speeding up if the acceleration is in the direction of motion, and slowing down if the acceleration is opposite the direction of motion. For example, a particle with negative velocity and negative acceleration is speeding up. But the particle is slowing down if the acceleration is positive, since it is being pushed in the positive direction (opposing its motion in the negative direction). We summarize this logic as follows.

- speeding up if its velocity and acceleration have the same sign.

- slowing down if its velocity and acceleration have opposite signs.

If a particle travels along a line with time \(t,\) as modeled by the position function \(s(t),\) then its velocity function is \(v(t) = \textderiv{s}{t}\) and its acceleration function is \(a(t)\) \(= \textderiv{v}{t}\) \(= \textderivOrder{s}{t}{2}.\) If \(s(t_1) = s_1\) and \(s(t_2) = s_2,\) where \(t_2 \gt t_1,\) then the particle's displacement on \([t_1, t_2]\) is \(\Delta s =\) \(s_2 - s_1.\) Since speed is the absolute value of velocity, we define a particle's speed function to be \(\abs{v(t)}.\) The times at which a particle changes direction correspond to the relative extrema of \(s(t);\) the object switches direction when the velocity function changes sign. In addition, a particle is

- speeding up if its velocity and acceleration have the same sign.

- slowing down if its velocity and acceleration have opposite signs.