4.4: Integration by Substitution

In Section 2.4 we differentiated composite functions. We now learn to integrate composite functions, which requires a variable change using a substitution. At the end of this section, you'll build your pattern recognition and be able to compute simple substitutions in your head. We discuss the following topics:

- Substitution Rule

- Integrating \(f(ax + b)\)

- Changing Bounds

- Integrals with Trigonometric Functions

- Integrals of Odd and Even Functions

Substitution Rule

The theme of the Integration chapter has been learning to go backward. The Chain Rule states that, for differentiable functions \(F\) and \(g,\) \begin{equation} \deriv{}{x} [F(g(x))] = F'(g(x)) \, g'(x) \pd \label{eq:chain-rule} \end{equation} Now let's discuss a strategy to transform \(F'(g(x)) \, g'(x)\) back to the composite function \(F(g(x)).\) Consider \begin{equation} \int F'(g(x)) \, g'(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:composite-integral} \end{equation} We know, from \(\eqref{eq:chain-rule},\) that this integral equals \(F(g(x)) + C.\) But we need to map the integral to this answer; we need to determine a procedure to allow antidifferentiation. We convert the integral into a simpler form by performing a substitution: Let \(u = g(x).\) Differentiating both sides of this equality gives \[\deriv{u}{x} = g'(x) \or \di u = g'(x) \di x \pd\] If we compare these components to \(\eqref{eq:composite-integral},\) then we see \[ \int F'(\underbrace{g(x)}_{u}) \, \underbrace{g'(x) \di x}_{\di u} = \int F'(u) \di u = F(u) + C \pd \] This substitution gave the much easier integral \(\int F'(u) \di u.\) Since \(u = g(x),\) reexpressing the answer in terms of \(x\) gives \[F(g(x)) + C \pd\] This procedure, called a \(\bf u\)-substitution (or using the Substitution Rule), enabled us to convert the integral in \(\eqref{eq:composite-integral}\) to the antiderivative \(F(g(x)) + C.\) Or if \(F' = f,\) then we can write the Substitution Rule as \begin{equation} \int f(g(x)) \, g'(x) \di x = \int f(u) \di u \label{eq:u-sub-f} \end{equation} if \(u = g(x).\)

Our strategy in integrating composite functions, therefore, is to let \(u\) be the inner function. The integrand should contain the derivative of the inner function; we then change the entire integral to be in terms of \(u,\) including the differential. This transformation gives us an easier integral. The full Substitution Rule is as follows.

When we perform a \(u\)-substitution, all quantities in the integral must be expressed in terms of \(u.\) No \(x\)-terms should remain; they must be converted to \(u.\) Think of the new integral as being in the \(u\)-world, since we perform the subsequent operations in terms of \(u.\)

Integrating \(f(ax + b)\)

Compare the result of Example 3 to the derivative \[\deriv{}{x} \par{e^{kx}} = k e^{kx} \pd\] When we differentiate \(e^{kx},\) we multiply by \(k;\) but when we integrate \(e^{kx},\) we divide by \(k.\) Let's generalize this notion: Consider the composite function \(f(ax + b)\) for \(a \ne 0.\) This family of functions appears frequently, so we want to easily recognize its derivatives and integrals. By the Chain Rule, if \(f\) is differentiable, then \[\deriv{}{x} [f(ax + b)] = af'(ax + b) \pd\] Instead of multiplying by \(a,\) we divide by \(a\) when we integrate: \begin{equation} \int f(ax + b) \di x = \tfrac{1}{a} F(ax + b) + C \pd \label{eq:int-reverse-chain} \end{equation}

PROOF To evaluate \(\int f(ax + b) \di x,\) we want to substitute the inner function \(ax + b,\) whose derivative is \(a.\) Thus, we rewrite the integral as \[\int \par{\tfrac{1}{a}} \, a f(ax + b) \di x \pd\] Now letting \(u = ax + b,\) we have \(\dd u = a \di x\) and so we see \[\int \tfrac{1}{a} f(\underbrace{ax + b}_{u}) \, \underbrace{a \di x}_{\dd u} = \tfrac{1}{a} \int f(u) \di u \pd \] If \(F\) is an antiderivative of \(f,\) then the integral becomes, for any value \(C,\) \[\tfrac{1}{a} F(u) + C = \tfrac{1}{a} F(ax + b) + C \pd\] \[\qedproof\]

- \(\ds \int \cos(3x + 1) \di x\)

- \(\ds \int (6x - 2)^3 \di x\)

- \(\ds \int \frac{1}{5x + 8} \di x\)

- The inner function \(3x + 1\) takes the form \(ax + b.\) An antiderivative of cosine is sine. Hence, by \(\eqref{eq:int-reverse-chain}\) the integral becomes \[\boxed{\tfrac{1}{3} \sin(3x + 1) + C}\]

- We identify the inner function to be \(6x - 2,\) which is linear. An antiderivative of \(u^3\) is \(u^4/4,\) so using \(\eqref{eq:int-reverse-chain}\) gives \[\tfrac{1}{6} \cdot \tfrac{1}{4} (6x - 2)^4 + C = \boxed{\tfrac{1}{24} (6x - 2)^4 + C}\]

- In the composite function, the inner function is \(5x + 8.\) An antiderivative of \(1/u\) is \(\ln \abs{u},\) so \(\eqref{eq:int-reverse-chain}\) gives \[\boxed{\tfrac{1}{5}\ln \abs{5x + 8} + C}\]

Changing Bounds

Consider the definite integral \[\int_a^b f(g(x)) g'(x) \di x \cma\] whose bounds are \(x = a\) and \(x = b.\) When we perform \(u\)-substitution on a definite integral, we need to convert everything to \(u,\) but the integral's bounds are in terms of \(x.\) Thus, if you substitute \(u = g(x),\) then you have two options: The first option is to write your answer in terms of \(x\) and substitute the bounds \(b\) and \(a.\) The second option is to change the bounds to be in terms of \(u \col\) When \(x = a,\) \(u = g(a);\) when \(x = b,\) \(u = g(b).\) The integral then becomes \[\int_{g(a)}^{g(b)} f(u) \di u \cma\] and you evaluate without converting back to \(x.\) Usually, the second option is easier.

We substitute \(u = x^3 + 1\) because \(\dd u = 3x^2 \di x.\) The term \(x^2\) appears in the integrand, so this substitution takes us into the \(u\)-world: \[\int \tfrac{1}{3} (\underbrace{x^3 + 1}_{u})^4 \, \underbrace{3x^2 \di x}_{\dd u} = \tfrac{1}{3} \int u^4 \di u \pd\] Thus, the definite integral becomes \[\tfrac{1}{3} \int_{x = 0}^{x = 1} u^4 \di u \pd\] We now have two subsequent options; this solution covers both methods.

Method 1 We find an antiderivative of \(u^4\) in terms of \(x.\) Doing so gives \[\tfrac{1}{5} u^5 + C = \tfrac{1}{5} (x^3 + 1)^5 + C \pd\] Now we use Part II of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus with our original bounds in terms of \(x \col\) \[ \ba \tfrac{1}{3} \int_{x = 0}^{x = 1} u^4 \di u &= \tfrac{1}{3} \cdot \tfrac{1}{5} (x^3 + 1)^5 \intEval_0^1 \nl &= \tfrac{1}{15} \parbr{(1^3 + 1)^5 - (0^3 + 1)^5} \nl &= \boxed{\tfrac{31}{15}} \ea \]

Method 2 After we perform the substitution to obtain the definite integral \(\tfrac{1}{3} \int_{x = 0}^{x = 1} u^4 \di u,\) we change the bounds to be in terms of \(u.\) When \(x = 0,\) \(u = 0^3 + 1 = 1;\) when \(x = 1,\) \(u = 1^3 + 1 = 2.\) Expressing the bounds in terms of \(u\) yields \[\tfrac{1}{3} \int_1^2 u^4 \di u \pd\] Now we integrate strictly with \(u\); we don't return to the \(x\)-world. We get \[ \ba \tfrac{1}{3} \cdot \tfrac{1}{5} u^5 \intEval_1^2 &= \tfrac{1}{15} (2^5 - 1^5) \nl &= \boxed{\tfrac{31}{15}} \ea \]

Integrals with Trigonometric Functions

In Section 4.1 we learned that \(\int \cos x \di x\) \(= \sin x + C\) and \(\int \sin x \di x\) \(= - \cos x + C.\) The Substitution Rule enables us to determine antiderivatives for the remaining four trigonometric functions: tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant.

Let's begin by determining an antiderivative for \(\cot x.\) Because \(\cot x\) \(= \cos x /\sin x,\) we have \[\int \cot x \di x = \int \frac{\cos x}{\sin x} \di x \pd\] We choose the substitution \(u = \sin x\) because the differential \(\dd u = \cos x \di x\) lies in the integral. Then the integral becomes \[\int \frac{1}{u} \di u = \ln \abs u + C = \ln \abs{\sin x} + C \pd\] To integrate secant, we employ a clever trick: We multiply the numerator and denominator by the sum \((\sec x + \tan x)\) to get \[\int \sec x \di x = \int \sec x \cdot \frac{\sec x + \tan x}{\sec x + \tan x} \di x = \int \frac{\sec^2 x + \sec x \tan x}{\sec x + \tan x} \di x \pd \] Letting \(u = \sec x + \tan x,\) we see \(\dd u = \par{\sec x \tan x + \sec^2 x} \di x\) and so the integral becomes \[ \int \frac{1}{u} \di u = \ln \abs u + C = \ln \abs{\sec x + \tan x} + C \pd \] The same tricks enable us to attain the antiderivatives of \(\tan x\) and \(\csc x.\)

The following table represents the integrals of all six trigonometric functions. In Sections 6.2 and 6.3, it will be essential to have them memorized.

| \(\ds \int \sin x \di x = -\cos x + C\) | \(\ds \int \cos x \di x = \sin x + C\) |

| \(\ds \int \tan x \di x = \ln \abs{\sec x} + C\) | \(\ds \int \cot x \di x = \ln \abs{\sin x} + C\) |

| \(\ds \int \sec x \di x = \ln \abs{\sec x + \tan x} + C\) | \(\ds \int \csc x \di x = - \ln \abs{\csc x + \cot x} + C\) |

Another common family of integrals contains polynomials in the denominator. To evaluate these integrals, we often complete the square (see Section 0.7) and then use the Substitution Rule; the result features inverse trigonometric functions. The following integrals are therefore useful for this procedure.

Integrals of Odd and Even Functions

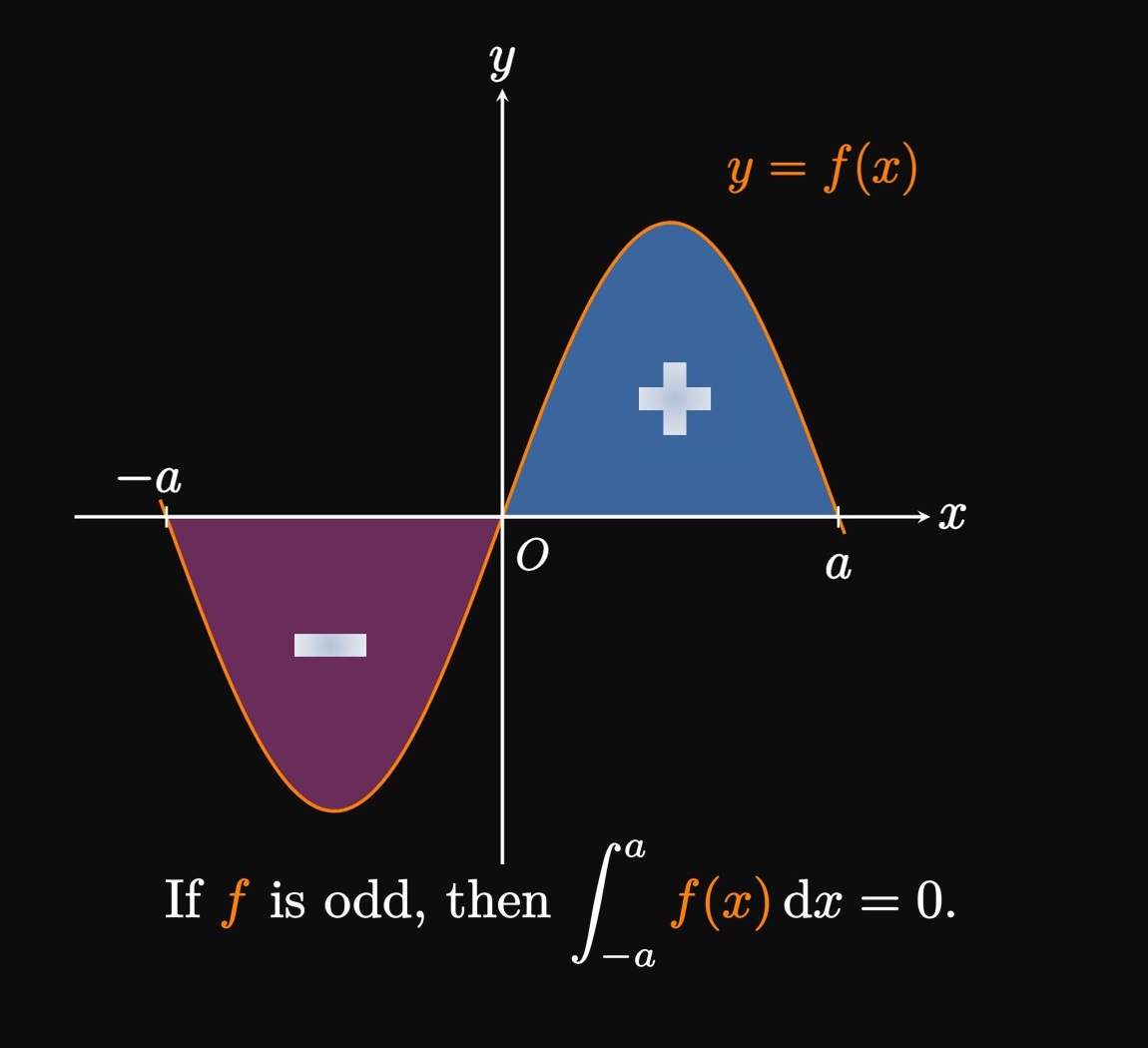

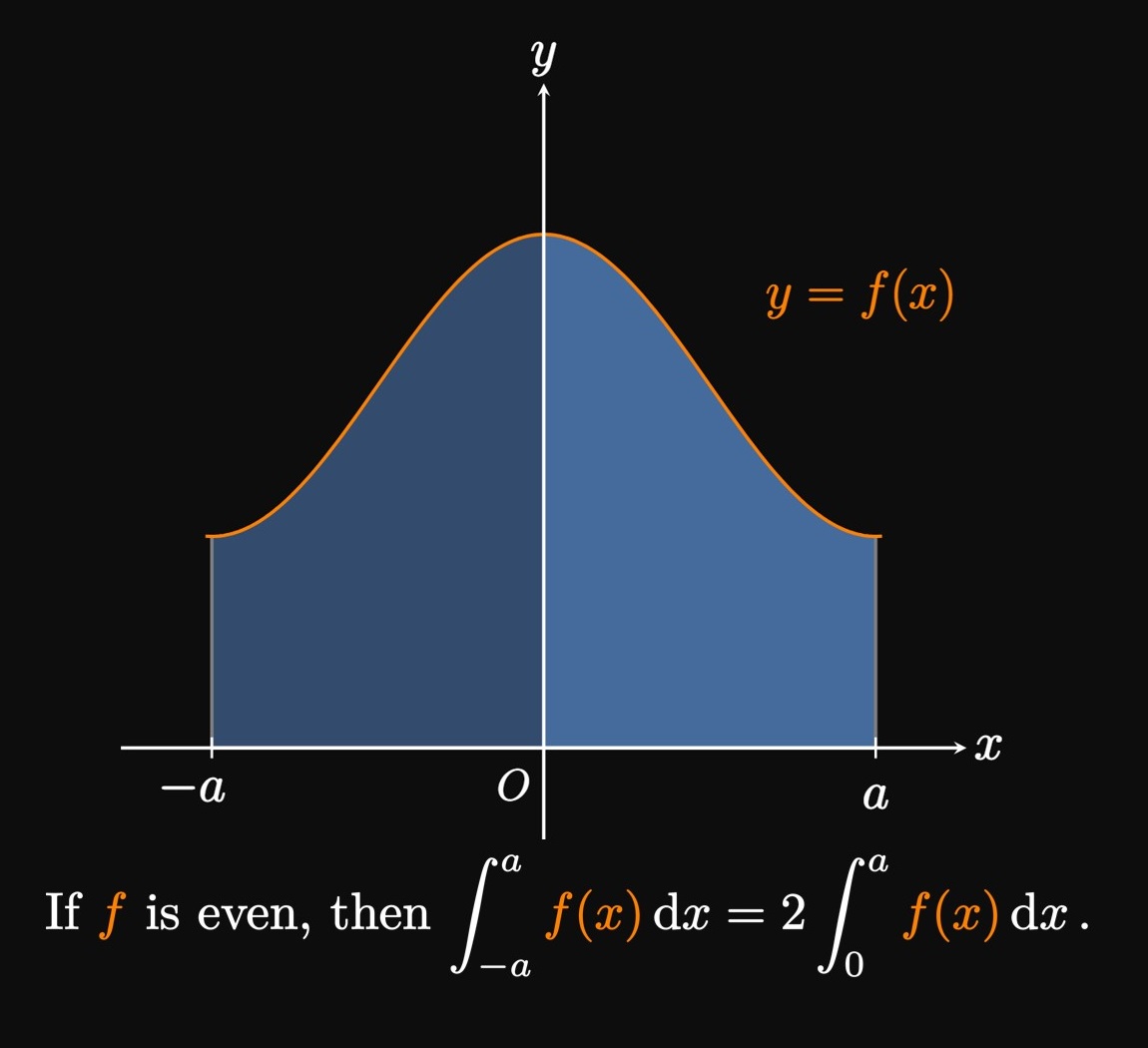

Many integral calculations are facilitated by using symmetry. Suppose that a function \(f\) is continuous on \([-a, a].\) Then the following properties help us evaluate \(\int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x.\)

- If \(f\) is odd, then \(\int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x\) \(= 0.\)

- If \(f\) is even, then \(\int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x\) \(= 2 \int_0^a f(x) \di x.\)

Recall that a definite integral equals a positive number if the region enclosed by \(f\) is above the \(x\)-axis, but a definite integral returns a negative number if the region is below the \(x\)-axis. In Figure 1A the region above the \(x\)-axis has the same area as the region below the \(x\)-axis. Thus, the signed areas cancel, so part (a) states that the integral equals \(0.\) For the special case of \(f(x) \geq 0\) on \([-a, a],\) part (b) says the area under \(f\) from \(-a\) to \(a\) is twice the area from \(0\) to \(a\) due to symmetry (Figure 1B).

PROOF Using the Additive Interval Property, we get \begin{align} \int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x &= \int_{-a}^0 f(x) \di x + \int_0^a f(x) \di x \nonum \nl &= -\int_0^{-a} f(x) \di x + \int_0^a f(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:int-split} \end{align} Substituting \(u = -x\) shows \(\dd u = -\dd x;\) when \(x = -a,\) \(u = a.\) Accordingly, we see \[-\int_0^{-a} f(x) \di x = -\int_0^a f(-u) (-\dd u) = \int_0^a f(-u) \di u \pd\] So \(\eqref{eq:int-split}\) becomes \begin{equation} \int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x = \int_0^a f(-u) \di u + \int_0^a f(x) \di x \pd \label{eq:int-split-2} \end{equation} If \(f\) is odd, then \(f(-u) = -f(u)\) and so \(\eqref{eq:int-split-2}\) becomes \[ \ba \int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x = - \int_0^a f(u) \di u + \int_0^a f(x) \di x = 0 \pd \ea \] Conversely, if \(f\) is even, then \(f(-u) = f(u)\) and so \(\eqref{eq:int-split-2}\) becomes \[\int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x = \int_0^a f(u) \di u + \int_0^a f(x) \di x = 2 \int_0^a f(x) \di x \pd\] \[\qedproof\]

Substitution Rule We use the Substitution Rule (also called \(\bf u\)-substitution) to integrate composite functions in which the derivative of the inner function lies in the integrand. Let \(g\) be a differentiable function whose range is an interval \(I,\) and let \(f\) be continuous over \(I.\) To evaluate the integral \(\int f(g(x)) \, g'(x) \di x,\) substitute \(u = g(x).\) Then \(\dd u = g'(x) \di x,\) and \[ \int f(g(x)) \, g'(x) \di x = \int f(u) \di u \pd \eqlabel{eq:u-sub-f} \]

Integrating \(f(ax + b)\) Let \(F\) be an antiderivative of \(f.\) If \(a \ne 0,\) then for any constant \(C,\) \[ \int f(ax + b) \di x = \tfrac{1}{a} F(ax + b) + C \pd \eqlabel{eq:int-reverse-chain} \]

Changing Bounds When we integrate \(\int_a^b f(g(x)) g'(x) \di x,\) we have a choice: The first option is to convert our final answer to \(x\) and substitute the bounds \(b\) and \(a.\) The second option is to change the bounds to be in terms of \(u \col\) \[\int_a^b f(g(x)) g'(x) \di x = \int_{g(a)}^{g(b)} f(u) \di u \cma\] and evaluate without converting back to \(x.\)

Integrals with Trigonometric Functions The following table shows the integrals for all six trigonometric functions:

| \(\ds \int \sin x \di x = -\cos x + C\) | \(\ds \int \cos x \di x = \sin x + C\) |

| \(\ds \int \tan x \di x = \ln \abs{\sec x} + C\) | \(\ds \int \cot x \di x = \ln \abs{\sin x} + C\) |

| \(\ds \int \sec x \di x = \ln \abs{\sec x + \tan x} + C\) | \(\ds \int \csc x \di x = - \ln \abs{\csc x + \cot x} + C\) |

When a polynomial is on the denominator, try completing the square, performing a substitution, and using one of the following formulas: \begin{align} \int \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - u^2}} \di u &= \asin u + C \cma \eqlabel{eq:int-asin} \nl \int \frac{1}{u^2 + 1} \di u &= \atan u + C \pd \eqlabel{eq:int-atan} \end{align}

Integrals of Odd and Even Functions Evaluating definite integrals is made easier through properties of symmetry. Let \(f\) be a continuous function on \([-a, a].\)

- If \(f\) is odd, then \(\int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x\) \(= 0.\)

- If \(f\) is even, then \(\int_{-a}^a f(x) \di x\) \(= 2 \int_0^a f(x) \di x.\)