9.6: Additional Calculus with Parametric and Polar

Parametric equations and polar functions expand our vision of calculus's uses. In the past few sections, we focused on this idea by differentiating and integrating parametric equations and polar functions. Now let's further extend our toolkit by discussing the following topics:

Arc Lengths in Parametric and Polar

In Section 7.1 we derived the following formula for the arc length of a smooth curve: \begin{equation} L = \int_a^b \sqrt{1 + \par{\deriv{y}{x}}^2} \di x \pd \label{eq:arc-length} \end{equation} Now let's modify this formula to be applicable to parametric equations and polar functions.

Parametric Equations

Suppose that a smooth curve is parameterized by the equations \(x = f(t)\)

and \(y = g(t),\) where \(\alpha \leq t \leq \beta.\)

(The word smooth means \(f'\) and \(g'\) are both continuous and not simultaneously \(0\) on

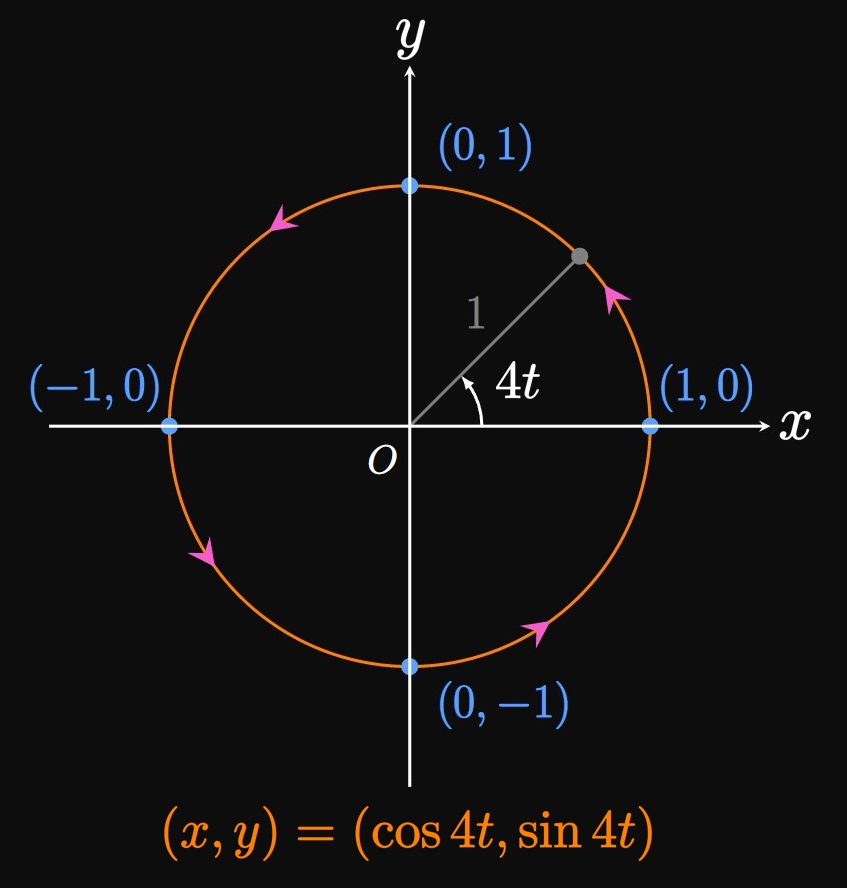

In Example 1 doubling the integral's upper bound would yield \[ \ba L &= \int_0^\pi \sqrt{(-4 \sin 4t)^2 + (4 \cos 4t)^2} \di t \nl &= \int_0^{\pi} 4 \di t = 4 \pi \pd \ea \] This result is twice the correct arc length because over \(0 \leq t \leq \pi\) the circle is traced twice, so the integral is double-counting. Therefore, ensure that the bounds traverse a parametric curve only once.

Polar Functions A polar function \(r = f(\theta)\) can be expressed parametrically as \[x = f(\theta) \cos \theta \and y = f(\theta) \sin \theta \cma\] where \(\theta\) is the parameter. Assuming that \(f'\) is continuous, let's use \(\eqref{eq:arc-length-para-leib}\) to derive a special expression for the arc length of a polar curve on \(\alpha \leq \theta \leq \beta.\) We treat \(\theta\) similarly to \(t,\) so our objective is to find an expression for \(\par{\textderiv{x}{\theta}}^2 + \par{\textderiv{y}{\theta}}^2.\) Differentiating shows \[ \ba \deriv{x}{\theta} &= f'(\theta) \cos \theta - f(\theta) \sin \theta \cma \nl \deriv{y}{\theta} &= f'(\theta) \sin \theta + f(\theta) \cos \theta \pd \ea \] Observe that \[ \ba \par{\deriv{x}{\theta}}^2 &= [f'(\theta)]^2 \cos^2 \theta - 2 f(\theta) f'(\theta) \sin \theta \cos \theta + [f(\theta)]^2 \sin^2 \theta \cma \nl \par{\deriv{y}{\theta}}^2 &= [f'(\theta)]^2 \sin^2 \theta + 2 f(\theta) f'(\theta) \sin \theta \cos \theta + [f(\theta)]^2 \cos^2 \theta \pd \ea \] Adding both equations, we get \[ \ba \par{\deriv{x}{\theta}}^2 + \par{\deriv{y}{\theta}}^2 &= [f(\theta)]^2 (\sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta) + [f'(\theta)]^2 (\sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta) \nl &= [f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2 \cma \ea \] where the last step is true by the Pythagorean identity. Since \(r = f(\theta)\) and \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} = f'(\theta),\) we write \[[f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2 = r^2 + \par{\deriv{r}{\theta}}^2 \pd\] Thus, \(\eqref{eq:arc-length-para-leib}\) gives the arc length to be \begin{equation} L = \int_\alpha^\beta \sqrt{r^2 + \par{\deriv{r}{\theta}}^2} \di \theta \pd \label{eq:arc-length-polar} \end{equation}

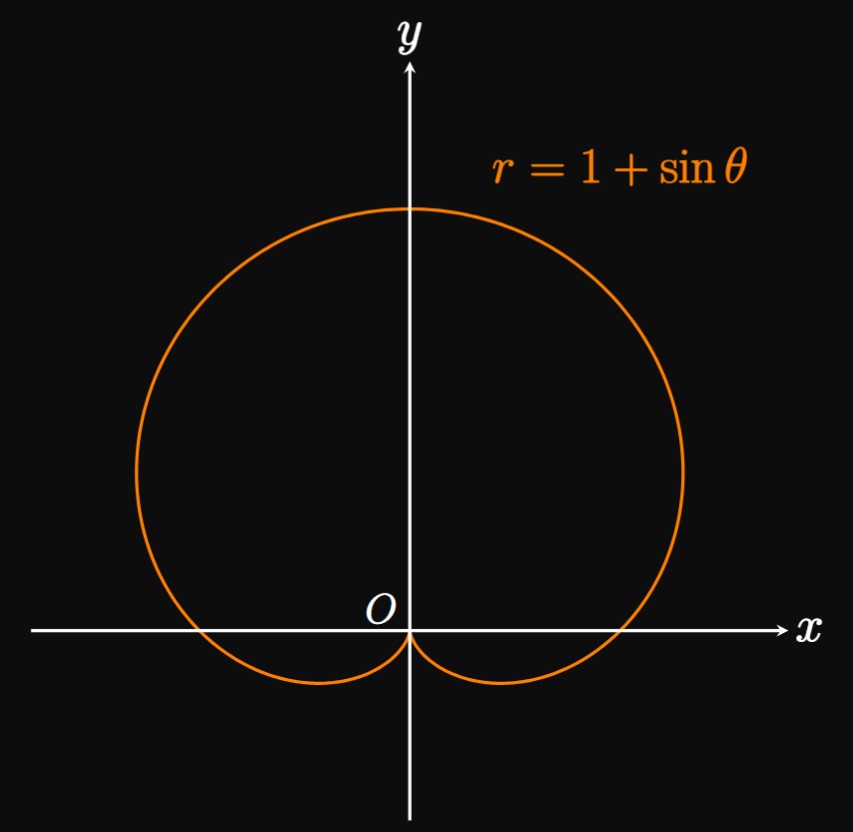

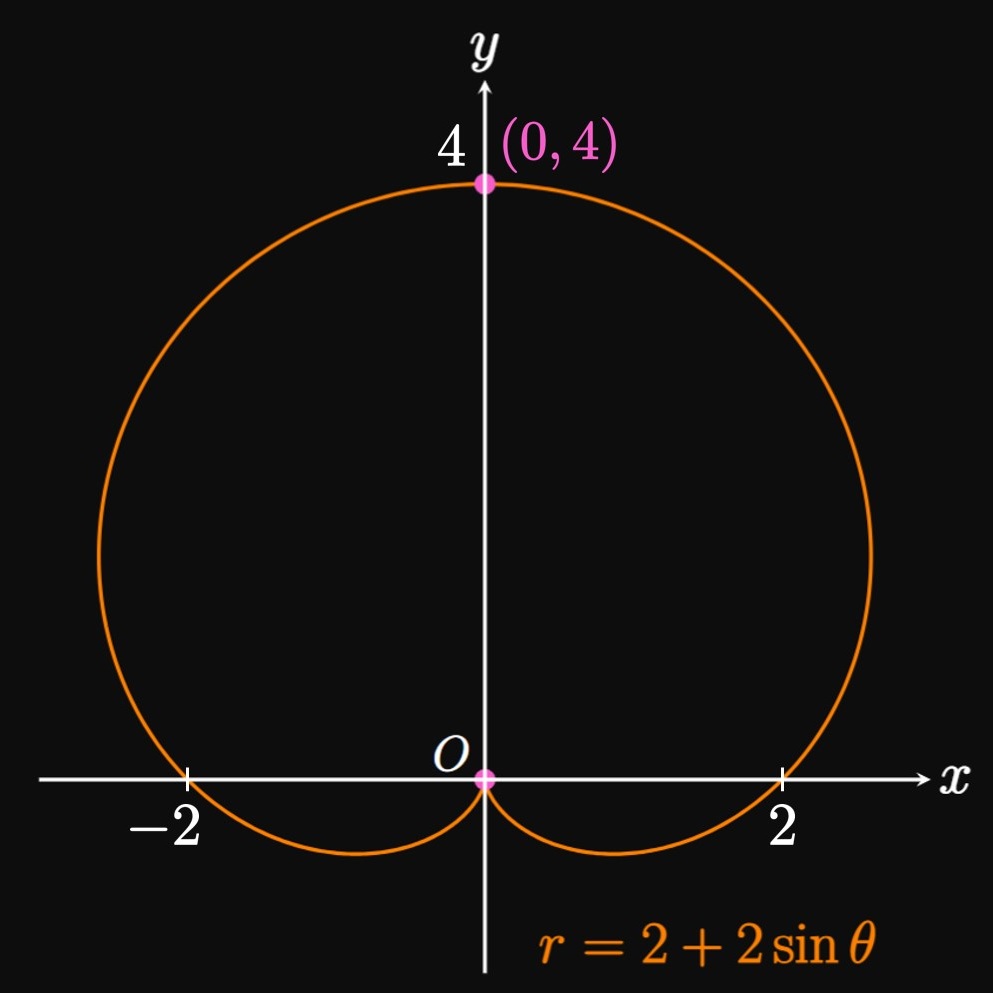

Integral Setup The graph of the cardioid is shown by Figure 2. We find \(\textderiv{r}{\theta} = \cos \theta,\) which is continuous, and \[ \ba r^2 &= (1 + \sin \theta)^2 = 1 + 2 \sin \theta + \sin^2 \theta \cma \nl \par{\deriv{r}{\theta}}^2 &= \cos^2 \theta \pd \ea \] Thus, we see \[ \ba r^2 + \par{\deriv{r}{\theta}}^2 &= 1 + 2 \sin \theta + \sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta \nl &= 2 + 2 \sin \theta \pd \ea \] The entire cardioid is traced out once over \(0 \leq \theta \leq 2 \pi,\) so \(\eqref{eq:arc-length-polar}\) gives \[L = \int_0^{2 \pi} \sqrt{2 + 2 \sin \theta} \di \theta \pd\]

Evaluating the Integral We multiply the numerator and denominator inside the radical by \(2 - 2 \sin \theta,\) as follows: \[ \ba \sqrt{\par{2 + 2 \sin \theta} \par{\frac{2 - 2 \sin \theta}{2 - 2 \sin \theta}}} &= \sqrt{\frac{4 - 4 \sin^2 \theta}{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \nl &= \sqrt{\frac{4 \cos^2 \theta}{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \nl &= \frac{2 \abs{\cos \theta}}{\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \pd \ea \] The integral therefore becomes \[ \ba L &= \int_0^{2 \pi} \frac{2 \abs{\cos \theta}}{\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \di \theta \nl &= \int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{2 \cos \theta}{\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \di \theta - \int_{\pi/2}^{3\pi/2} \frac{2 \cos \theta}{\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \di \theta + \int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi} \frac{2 \cos \theta}{\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \di \theta \cma \ea \] where the last step is true because \(\cos \theta \lt 0\) on \((\pi/2, 3\pi/2).\) To antidifferentiate \((2 \cos \theta)/\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta},\) we substitute \(u = 2 - 2 \sin \theta.\) Then \(\dd u = -2 \cos \theta \di \theta,\) so we see \[ \ba \int \frac{2 \cos \theta}{\sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \di \theta &= \int \frac{-1}{\sqrt u} \di u \nl &= -2 \sqrt{u} + C \nl &= -2 \sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta} + C \pd \ea \] We therefore find the arc length to be \[ \ba L &= \par{-2 \sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \intEval_0^{\pi/2} - \par{-2 \sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \intEval_{\pi/2}^{3\pi/2} + \par{-2 \sqrt{2 - 2 \sin \theta}} \intEval_{3\pi/2}^{2 \pi} \nl &= \par{0 + 2 \sqrt 2} - \par{-4 + 0} + \par{-2 \sqrt 2 + 4} = \boxed 8 \ea \]

Surface Areas of Revolution in Parametric and Polar

In Section 7.2 we attained the following formulas for surface areas of revolution around an axis: \begin{alignat*}{2} S &= \int_a^b 2 \pi y \di s \cma \lspace &&[\text{Rotating about } x \text{-Axis}] \nl S &= \int_c^d 2 \pi x \di s \pd \lspace &&[\text{Rotating about } y \text{-Axis}] \end{alignat*} Let's suppose that a smooth curve \(C,\) parameterized by \(x = f(t)\) and \(y = g(t),\) is revolved around the \(x\)- or \(y\)-axis. Then we modify the preceding formulas by substituting \(x = f(t)\) or \(y = g(t)\) and using the differential arc length segment \[\dd s = \sqrt{[f'(t)]^2 + [g'(t)]^2} \di t \pd\] Doing so produces the following formulas: \begin{alignat}{2} S &= \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi g(t) \sqrt{[f'(t)]^2 + [g'(t)]^2} \di t \cmaa g(t) \geq 0 \cma \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } x \text{-Axis}] \label{eq:S-parametric-x} \nl S &= \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi f(t) \sqrt{[f'(t)]^2 + [g'(t)]^2} \di t \cmaa f(t) \geq 0 \pd \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } y \text{-Axis}] \label{eq:S-parametric-y} \end{alignat}

A similar strategy enables us to find surface areas of revolution with polar functions. By substituting \(x = f(\theta) \cos \theta\) and \(y = f(\theta) \sin \theta\) and the differential arc length segment \[\dd s = \sqrt{r^2 + \par{\deriv{r}{\theta}}^2} \di \theta = \sqrt{[f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2} \cma\] we attain the following equations, assuming \(f(\theta) \geq 0 \col\) \begin{alignat}{2} S &= \small \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi f(\theta) \sin \theta \sqrt{[f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2} \di \theta \cmaa f(\theta) \sin \theta \geq 0 \cma \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } x \text{-Axis}] \label{eq:S-polar-x} \nl S &= \small \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi f(\theta) \cos \theta \sqrt{[f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2} \di \theta \cmaa f(\theta) \cos \theta \geq 0 \pd \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } y \text{-Axis}] \label{eq:S-polar-y} \end{alignat}

Arc Lengths in Parametric and Polar Special formulas enable us to find arc lengths of curves described by parametric equations or polar functions. Let \(C\) be a curve parameterized by the equations \(x = f(t)\) and \(y = g(t)\) for \(\alpha \leq t \leq \beta.\) If \(f'\) and \(g'\) are continuous on this interval, then the arc length of \(C\) is \begin{equation} L = \int_\alpha^\beta \sqrt{[f'(t)]^2 + [g'(t)]^2} \di t \pd \eqlabel{eq:arc-length-parametric} \end{equation} This formula assumes \(C\) is traversed once. In Leibniz notation, we write \begin{equation} L = \int_\alpha^\beta \sqrt{\par{\deriv{x}{t}}^2 + \par{\deriv{y}{t}}^2} \di t \pd \eqlabel{eq:arc-length-para-leib} \end{equation} Alternatively, suppose that a polar function \(r = f(\theta)\) has a continuous derivative on \([\alpha, \beta].\) The curve's arc length on \(\alpha \leq \theta \leq \beta,\) assuming that the curve is traversed only once, is \begin{equation} L = \int_\alpha^\beta \sqrt{r^2 + \par{\deriv{r}{\theta}}^2} \di \theta \pd \eqlabel{eq:arc-length-polar} \end{equation} In each case, ensure that the curve does not cross itself to avoid double-counting.

Surface Areas of Revolution in Parametric and Polar We have specialized equations that provide us the surface areas of revolution for parametric or polar curves. If a smooth curve \(C\) parameterized by \(x = f(t)\) and \(y = g(t)\) does not cross itself over \(\alpha \leq t \leq \beta,\) then the surface area of revolution generated by rotating \(C\) about each axis is given by the following formulas: \begin{alignat}{2} S &= \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi g(t) \sqrt{[f'(t)]^2 + [g'(t)]^2} \di t \cmaa g(t) \geq 0 \cma \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } x \text{-Axis}] \eqlabel{eq:S-parametric-x} \nl S &= \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi f(t) \sqrt{[f'(t)]^2 + [g'(t)]^2} \di t \cmaa f(t) \geq 0 \pd \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } y \text{-Axis}] \eqlabel{eq:S-parametric-y} \end{alignat} Conversely, if \(f(\theta)\) is a polar function whose derivative is continuous on \([\alpha, \beta],\) then the surface area of revolution formed by revolving the curve \(r = f(\theta),\) \(\alpha \leq \theta \leq \beta,\) around an axis, assuming that the curve does not cross itself, is given by one of the following formulas: \begin{alignat}{2} \small S &= \small \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi f(\theta) \sin \theta \sqrt{[f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2} \di \theta \cmaa f(\theta) \sin \theta \geq 0 \cma \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } x \text{-Axis}] \eqlabel{eq:S-polar-x} \nl \small S &= \small \int_\alpha^\beta 2 \pi f(\theta) \cos \theta \sqrt{[f(\theta)]^2 + [f'(\theta)]^2} \di \theta \cmaa f(\theta) \cos \theta \geq 0 \pd \qquad &&[\text{Rotating about } y \text{-Axis}] \eqlabel{eq:S-polar-y} \end{alignat}