Chapter 2 Challenge Problems Solutions

- Calculate the maximum height of the central arch.

- At what points is the height \(80\) meters?

- Calculate the slope of the arch at the points in part (b).

- The maximum height occurs when \(x = 0 \col\) \[ \ba y &= 211.49 - 20.96 \cosh 0 \nl &= 211.49 - 20.96 = \boxed{190.53 \un{m}} \ea \] (Note: The Gateway Arch's maximum height is \(192 \un{m},\) but the central arch is \(190.53 \un{m}\) tall.)

- Using a graphing calculator, we find the solutions of \[y = 211.49 - 20.96 \cosh 0.03291765x = 80\] to be \(x = \pm 76.647.\) Hence, the central curve is \(80 \un{m}\) tall at the points located \(76.647 \un{m}\) from the center.

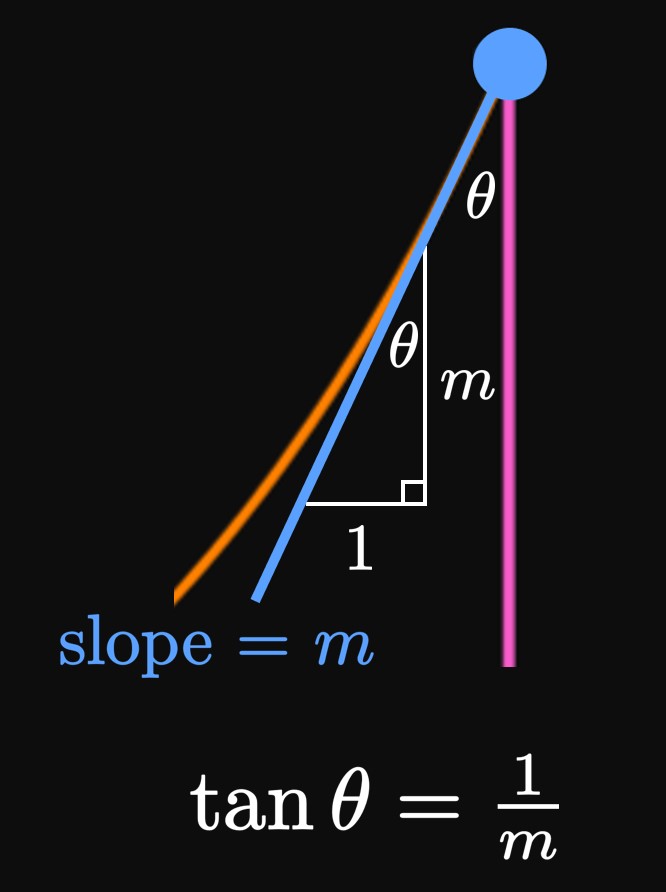

- The derivative function is \[ \ba y' &= -20.96(0.03291765) \sinh 0.03291765x \nl &= -0.689953944 \sinh 0.03291765x \pd \ea \] So at \(x = \pm 76.747,\) the slopes are \[ \ba y'(\pm 76.647) &= -0.689953944 \sinh 0.03291765 (\pm 76.647) \nl &\approx \mp 4.273 \pd \ea \] So the slope at \((-76.747, 80)\) is approximately \(4.273,\) and the slope at \((76.747, 80)\) is approximately \(-4.273.\)

Even \(n\) The second derivative of \(f\) has a negative sign, but its fourth derivative has a positive sign. Likewise, \(n = 6\) features a negative sign and \(n = 8\) has a positive sign. The pattern for this sign alternation is represented by \[(-1)^{n/2} \pd\] Thus, we conclude that \[f^{(n)}(x) = \boxed{(-1)^{n/2} k^n \sin kx \cmaa n \textrm{ even}}\]

Odd \(n\) The first derivative of \(f\) has a positive sign, but its third derivative has a negative sign. If we kept repeating the pattern, then we would have a positive sign for \(n = 5\) and a negative sign for \(n = 7.\) The pattern for this sign alternation is represented by \[(-1)^{1 + (n + 1)/2} = (-1)^{(n - 1)/2} \pd\] Thus, we have \[f^{(n)}(x) = \boxed{(-1)^{(n - 1)/2} k^n \cos kx \cmaa n \textrm{ odd}}\]

- Calculate \(\lim_{k \to \infty} c.\)

- Show that \(\lim_{k \to 0^+} c = -\infty.\) What does this result mean geometrically?

- Using differentials, approximate the amount by which \(c\) changes as \(k\) increases from \(2\) to \(2.1.\)

- With \(a\) held constant, the value of \(k\) increases at a constant rate of \(2\) units per minute. When \(k = 4,\) how quickly is \(c\) changing with time?

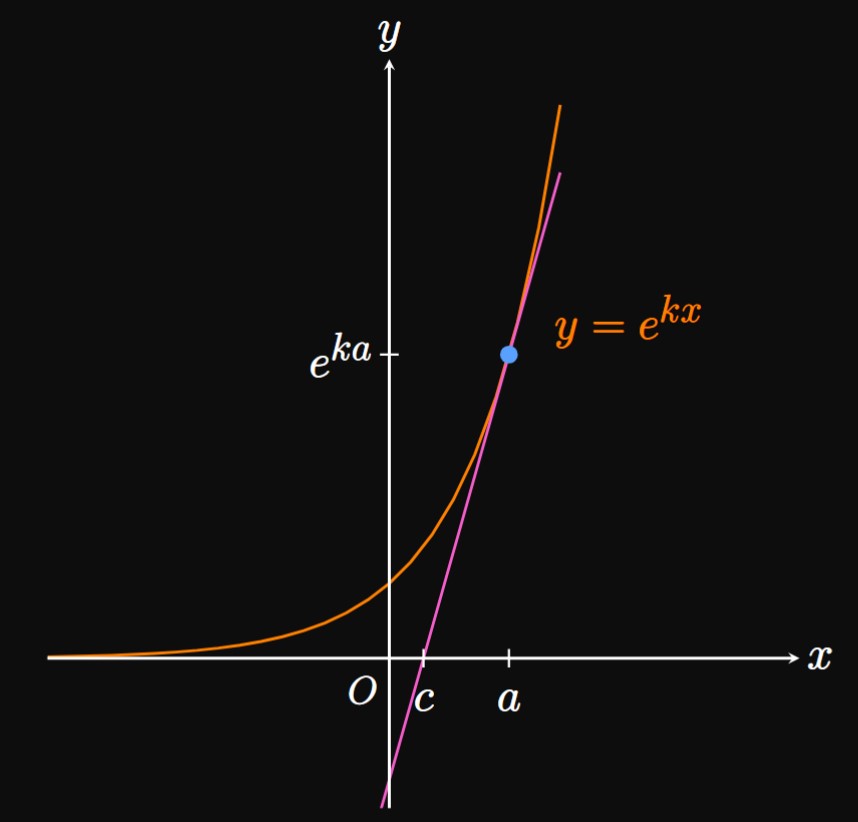

- We have \(f'(x) = ke^{kx}.\) So an equation of the line tangent to \(f\) at \((a, e^{ka})\) is \[y - e^{ka} = k e^{ka} (x - a) \pd\] This line has an \(x\)-intercept at \(x = c,\) so substituting \((c, 0)\) gives \[ \ba 0 - e^{ka} &= k e^{ka} (c - a) \nl \implies c &= a - \frac{1}{k} \pd \ea \] Then \[ \ba \lim_{k \to \infty} c &= \lim_{k \to \infty} \par{a - \frac{1}{k}} \nl &= \boxed a \ea \] This result is logical: as \(k\) increases, the curve \(f\) becomes steeper and so \(\ell\) becomes closer to the vertical line \(x = a.\)

-

As \(k \to 0^+,\) \(1/k \to \infty.\)

Accordingly, as requested,

\[\underbrace{a - \frac{1}{k}}_{c} \to -\infty \as k \to 0^+ \pd\]

Geometrically, \(k \to 0^+\) means the curve \(f(x) = e^{kx}\)

becomes flatter,

so line \(\ell\) becomes more horizontal.

By making \(k\) arbitrarily close to \(0\) (with

\(k \gt 0\)), the \(x\)-intercept of line \(\ell\) continually shifts to the left, away from the \(y\)-axis. - Differentiating both sides of \(c = a - 1/k\) with respect to \(k,\) we get \[ \ba \deriv{c}{k} &= \frac{1}{k^2} \nl \implies \dd c &= \frac{1}{k^2} \di k \pd \ea \] Taking \(k = 2,\) \(\Delta c \approx \dd c,\) and \(\di k = \Delta k\) \(= 0.1,\) we have \[\Delta c \approx \frac{1}{(2)^2} (0.1) = \boxed{\frac{1}{40}}\]

- Differentiating both sides of \(c = a - 1/k\) with respect to time, and noting that \(a\) is constant, we get \[ \deriv{c}{t} = \frac{1}{k^2} \deriv{k}{t} \pd \] We are given \(\textderiv{k}{t} = 2\) and \(k = 4,\) which we substitute to get \[ \ba \deriv{c}{t} \intEval_{k = 4} = \frac{1}{4^2} (2) = \boxed{\frac{1}{8}} \ea \]

- Show that \[f'(x) = \frac{-2x - 4}{\par{x^2 + 4x + k}^2} \pd\]

- If \(k = 4,\) then find the only vertical asymptote to the graph of \(y = f(x).\)

- For \(k \ne 4,\) determine the \(x\)-coordinate at which the graph of \(y = f(x)\) has a horizontal tangent.

- Determine and interpret \[\lim_{x \to -\infty} f'(x) \and \lim_{x \to \infty} f'(x) \pd\]

- Show that \(f\) has no vertical asymptotes if \(k \gt 4.\)

- The Quotient Rule gives the derivative of \(f\) to be \[ \ba f'(x) &= \frac{(0) \par{x^2 + 4x + k} - 1(2x + 4)}{\par{x^2 + 4x + k}^2} \nl &= \frac{-2x - 4}{\par{x^2 + 4x + k}^2} \cma \ea \] as requested.

- If \(k = 4,\) then \(f\) becomes \[f(x) = \frac{1}{x^2 + 4x + 4} \pd\] The function \(f\) has a vertical asymptote when its denominator is \(0\) but its numerator is nonzero. So we equate the denominator to \(0\) to find \[ \ba x^2 + 4x + 4 &= 0 \nl (x + 2)^2 &= 0 \nl \implies x &= -2 \pd \ea \] Thus, the only vertical asymptote to the graph of \(f\) for \(k = 4\) is \(\boxed{x = -2}.\)

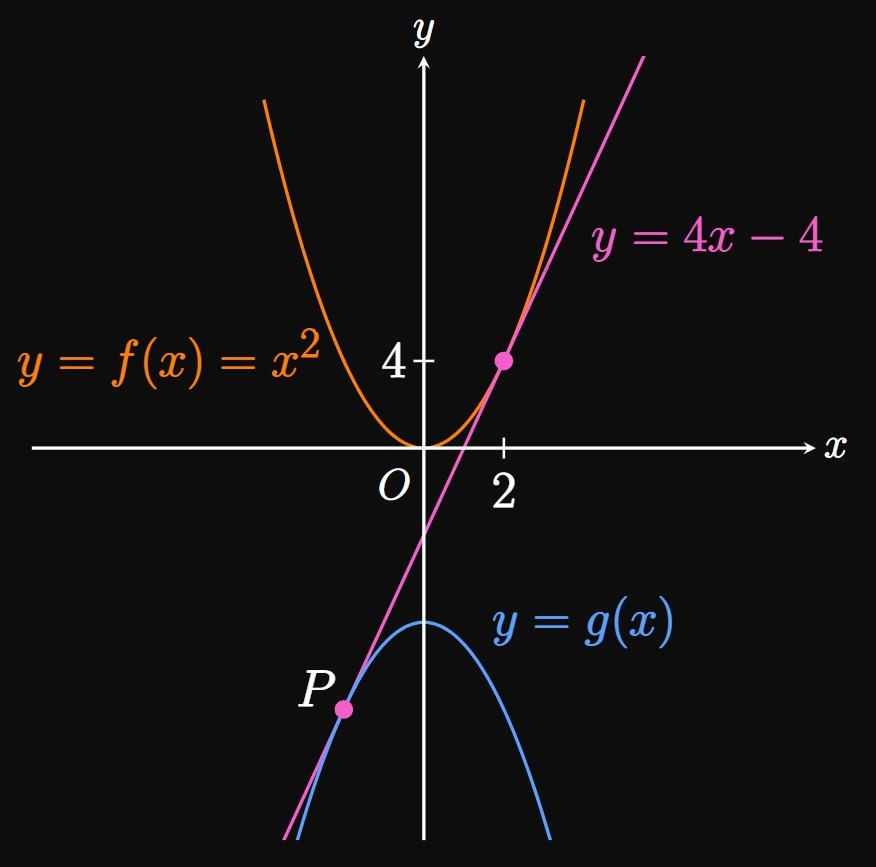

- The graph of \(f\) has a horizontal tangent at some \(x\) if and only if \(f'(x) = 0.\) We see \[f'(x) = \frac{-2x - 4}{\par{x^2 + 4x + k}^2} = 0 \implies \boxed{x = -2}\] Thus, the family of graphs \(f(x) = 1/(x^2 + 4x + k)\) has a horizontal tangent at \(x = -2\) if \(k \ne 4,\) but has a vertical asymptote if \(k = 4.\)

- Observe that the denominator of \(f'\) has a higher degree than the numerator of \(f'.\) Hence, the denominator grows faster than the numerator as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty,\) pushing the value of \(f'\) toward \(0.\) Accordingly, \[\lim_{x \to -\infty} f'(x) = 0 \and \lim_{x \to \infty} f'(x) = 0 \pd\] These limits tell us that the slope to \(f\) approaches \(0\) as \(x \to \infty\) or \(x \to -\infty.\) The graph of \(f\) has one horizontal asymptote, \(y = 0,\) so the slope approaching \(0\) is expected as \(x\) approaches infinity or negative infinity.

- The graph of \(f(x) = 1/(x^2 + 4x + k)\) has no vertical asymptotes if and only if the quadratic equation \(x^2 + 4x + k = 0\) has no real solutions. The discriminant of the quadratic is \[(4)^2 - 4(1)(k) = 16 - 4k \pd\] (See Section 0.7 to review how the discriminant shows how many real zeros a quadratic has.) If the quadratic equation has no real solutions, then the discriminant must be negative: \[16 - 4k \lt 0 \implies k \gt 4 \pd\] Thus, \(f(x) = 1/(x^2 + 4x + k)\) has no vertical asymptotes for \(k \gt 4\) because its denominator is never \(0.\)

- Solving \(f' = g',\) we see \[ \ba x^3 + 12 &= 3x^2 + 4x \nl x^3 - 3x^2 - 4x + 12 &= 0 \nl x^2 (x - 3) - 4(x - 3) &= 0 \nl (x - 3) (x^2 - 4) &= 0 \nl \implies x &= -2 \cma x = 2 \cma x = 3 \pd \ea \]

- Equating \(f' = h',\) we see \[ \ba x^3 + 12 &= 4x + 27 \nl x^3 - 4x - 15 &= 0 \pd \ea \] Out of all the solutions from the first case—that is, \(x = -2,\) \(x = 2,\) and \(x = 3\)—only \(x = 3\) solves this equation.

- We solve \(g' = h',\) as follows: \[ \ba 3x^2 + 4x &= 4x + 27 \nl x^2 &= 9 \nl \implies x &= -3 \cma x = 3 \pd \ea \]